One difficulty reviewing Larry Alex Taunton’s new book—The Faith of Christopher Hitchens: The Restless Soul of the World’s Most Notorious Atheist—is deciding on a genre. While the back of the book categorizes it as “Biography/Autobiography/Religious,” I’ve decided it primarily belongs to a time-honored American storytelling tradition: the road trip.

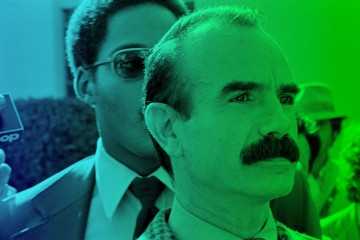

Christopher Hitchens was a towering public intellectual, renowned for his virulent hatred of religion. He was, as Taunton puts it, “Public Enemy Number One” in the minds of many Christians. That’s easy to understand, given his public persona as a rapier-tongued debater who relished humiliating all comers. What’s far less known is that Hitchens developed deep personal relationships with a number of evangelical Christians, including Taunton. And this was not by accident. Hitchens actively cultivated them.

Unlikely Friendship

Readers may be initially skeptical of The Faith of Christopher Hitchens. There’s something unseemly about “tell all” books that reveal confidences and appear to attempt to profit by association with celebrity. Taunton—who is founder and executive director of Fixed Point Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to the public defense of the Christian faith—is well aware of the pitfalls and, in fact, initially shared the hesitations. He had no interest in writing it, but his editor convinced him his relationship with Hitchens—a subject of “endless fascination to many”—was worthy of explanation.

The book describes a friendship between two people of diametrically opposite beliefs—a timely topic given the radical polarization generally evident these days. Taunton handles the confidentiality issue with care; many personal details about Hitchens’s life are not addressed, particularly with respect to his wife and children. When not writing with firsthand knowledge (i.e., personal conversations), Taunton generally sticks to the public record, whether magazine articles, newspaper columns, or Hitchens’s autobiography Hitch-22.

Many have noted that Hitchens was a man of contradictions. Taunton summarizes them: “a Marxist in youth who longed for acceptance among the social elites; a peacenik who revered the military; a champion of the Left who was nonetheless pro-life, pro-war-on-terror, and after 9/11 something of a neocon.”

Hitchens himself repeatedly spoke of how, from an early age, he had learned to “keep two sets of books.” There was a marked distinction between Hitchens’s public persona and his private life. And in his final years, Taunton was uniquely privileged to know the latter. He discovered a remarkable thing: the man who’d made a major public defection from the Left after 9/11 was a privately conflicted soul contemplating an even bigger defection. To help him navigate clearly and weigh the costs, he chose an evangelical Christian from the heart of the Bible Belt.

Hitchens’s fans might find that revelation shocking, but Taunton is hardly the caricature of an ignorant backwoods Bible thumper. As founder of the Fixed Point Foundation, he had gained the respect of many leading thinkers with whom he’d organized and moderated debates: Richard Dawkins, John Lennox, David Berlinski, Michael Schermer, and, of course, Hitchens himself. In Taunton, Hitchens found a friend who also happened to be a gifted apologist at the highest level.

Five Observations

Reluctant to spoil anything for readers, I’ll make a few observations to whet the appetite.

First, Taunton’s portrait of Hitchens, which traces back to his earliest years, is without caricature. Taunton simply has the measure of the man—the sarcasm, wit, humor, arrogance—and by the end we feel as if we really know him. Nothing seems false or exaggerated; it’s an honest and bracing treatment.

Second, The Faith of Christopher Hitchens extracts an often-forgotten truth: unbelief is rarely (if ever) a purely intellectual matter. Hitchens was influenced in his youth by many factors, not least of which is a particularly appalling stint at an English boarding school where he learned to loathe phony self-righteousness and cheap dogma. He was hardly exposed to healthy Christianity—if it was Christianity at all. Hitchens’s complicated relationship with his father (he greatly disrespected him), the fawning from his mother, his natural skill with words—all this led to an unhealthy arrogance at a young age. It’s a good reminder: nobody arrives at atheism by merely weighing the intellectual merits.

Third, Hitchens was rocked to the core by 9/11 because he came face-to-face with real evil, and he couldn’t stand with fellow leftists looking for any and every reason to excuse the perpetrators. While he continued trying to wield the “Problem of Evil” as a weapon against Christianity, in truth that sword was double-edged. It posed an insurmountable problem for his atheism. Taunton makes clear that Hitchens knew this. Observers often noticed he routinely skirted the problem of moral order in an atheist universe by changing the subject. This was on purpose.

Fourth, one shouldn’t take biblical literacy for granted, even when it comes to one of the world’s great public intellectuals. Hitchens’s familiarity with the Bible was shockingly shallow. Rather than mock, berate, or shame, Taunton invited Hitchens to study the Bible with him.

Fifth, Taunton’s book is a reminder that apologetics is never about winning arguments; it’s about winning people. By the end, Taunton was unafraid to boldly press the matter of repentance and trust in Jesus in a sobering, poignant, and vulnerable way. The “public” Hitchens—the sneering-and-jeering Hitchens—might have taken this effort as an affront. But the bonds of friendship and trust between them formed a context in which the real Hitchens clearly appreciated it.

Compelling Story

The book’s overall genius is that it’s a story. An immensely compelling, page-turning, cannot-put-down kind of story. Yes, it includes all kinds of stimulating intellectual fodder, but it’s really about two friends who deeply respect each other: the hardened atheist and the fervent Christian evangelist.

After Hitchens was diagnosed with what amounted to a death sentence (esophageal cancer), he undertook two private road trips with Taunton: one through the Shenandoah Valley, and another through Montana and Yellowstone Park. The purpose of these trips was to study the Gospel of John together. Taunton’s recounting of these trips is at times hilarious (the clean Southern evangelical driving, and the hard-scrabble atheist in the passenger seat with an open Bible, whisky, and cigarette), at times tension-filled, and often deeply moving.

If you’re looking for a melodramatic Christopher Hitchens “conversion story,” this isn’t it. If you’re looking for a “how-to” apologetics manual of decisive arguments, this isn’t it. But if you’re looking for a beautiful model of what charity, friendship, and evangelism ought to look like, this book is for you.

With its unique combination of superb storytelling, intellect, and passion, The Faith of Christopher Hitchens achieves—and deserves—the rare status of instant classic.