I sat half asleep in the front passenger seat of a Hyundai SUV looking out of the window listlessly, only vaguely aware of the countryside through which we were passing. The warmth of the car and the bright sunshine belied a colder and grimmer reality. I was jostled from this gentle slumber as the car braked heavily. Before us stood two soldiers of the South Korean 25th Infantry Division, one hand up ordering us to stop and the other gripping a Daewoo K2 assault rifle. Wearing full combat gear with only their eyes visible behind the black masks they wore to protect them from the bitter wind, one stood

behind a maze of concrete and steel barriers while the other approached the Hyundai cautiously. My driver, Don, himself a former member of the Republic of Korea Army (ROKA), cracked the window and presented a special permit granting us access to this remote portion of the DMZ. The soldier disappeared into a guardhouse to make a phone call while his companion kept us under close watch.

“We are to wait here while he checks us out,” Don said.

The ROKA soldier assigned to keep a close eye on us. He was a delightful young man.

Don is not his real name. Like many Koreans who interact with Westerners regularly, he has adopted a pseudonym that his clients can more easily pronounce than his actual Korean name. The hotel concierge is, say, Jim and the woman at the check-in desk is

Angela—but not really.

After a delay of twenty minutes or so, a Jeep arrived, and another soldier got out and walked purposefully in our direction. Emerging from the guardhouse, soldier no. 1 returned our permit, told us we were approved, and fitted a flag to the car door and put a placard on our dashboard. He then informed us that this newly arrived soldier would accompany us to make sure we didn’t get lost or hurt. Landmines are, after all, strewn all over the DMZ, and those occupying the 150 guard posts on the north side of the wire have been known to shoot more than a few people on the southern side. Indeed, since the Korean War ended in July 1953, more than a thousand South Koreans, Americans, and other citizens of countries that comprise the forces of the United Nations have been killed along this dangerous stretch of hotly contested land. As recently as 2015, North Korea lobbed a few shells into a nearby village to destroy, of all things, loudspeakers blasting K-Pop. I’ve heard of asking your neighbors to turn down their music, but this is a bit extreme.

A South Korean guard tower in the foreground and, across the Imjin River, North Korea. With field glasses you can see the soldiers on the other side.

But this soldier’s real job was, I suspect, to make sure we didn’t do some damned silly thing to provoke an international incident. He got into the backseat of the car and directed us through the barrier and up a mountainside. We parked just below a ROKA guard post manned by soldiers carrying the same K2s slung over their backs as they stood behind mounted machine guns whose barrels pointed menacingly northward.

“No photo,” the soldier said as we got out of the car. It seems like an antiquated rule in the age of satellites and drones, but I dutifully obey.

Nobel Prize-winning author Alexander Solzhenitsyn once said that the line between good and evil runs through every human heart. Here it runs through the Korean Peninsula. The DMZ—Demilitarized Zone—is a 250-kilometer long and 4-kilometer wide border cutting Korean in half. Calling it demilitarized is a bit of dark humor. This place bristles with weapons. With the use of a pair of field glasses, I could see the guard posts of the North Korean People’s Army (KPA) across the wide expanse of this No Man’s Land, and if you looked very carefully, you could even make out the dark figures of the sentries themselves. Spanning the western and eastern horizons are the barbed wire and earthen walls rolling over distant hills on the South Korean side of the DMZ, machine gun towers perforating the otherwise unbroken line at regular intervals.

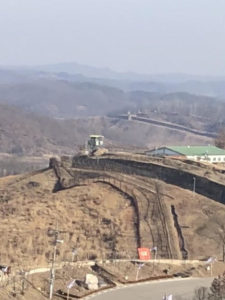

The barbed wire and earth wall and machine gun towers on the South Korean side.

That is not all.

Roads, bridges, and any potential path that KPA troops and tanks might follow southward (as they did in June 1950) are mined with explosive charges that will be detonated in the event of war, thus slowing—one hopes—any advance on Seoul. On the southern side, squat trees and bushes populate the gray landscape; on the northern side, there is nothing but grass and dirt as all vegetation has been flattened to provide clear sightlines for North Korean machine gunners. On the southern side, a free society flourishes economically, politically, culturally; on the northern side lies a human and economic wasteland ruled by a hardline communist regime. The DMZ, stretching roughly along the infamous 38th parallel, has been one of the most dangerous borders in the world and the spot many fear will be the flashpoint for the next World War.

It’s eerie.

Adding to the eerie quality is the ominous silence. But there was something else, and it took me a while to identify it. All of this felt like an anachronism, an embarrassing relic of the Cold War that should have fallen in November 1989 along with the Berlin Wall. Didn’t the reunification and freedom fervor that swept Germany three decades ago penetrate these remote regions of Asia? When Berliners were rocking to the music of the Scorpions, the North Koreans were still goose-stepping to the awkward beat of communist propaganda. Apparently, Reagan needed to make a visit here, too:

“Mr. Kim Il-Sung, open this gate! Mr. Kim Il-Sung, tear down this wall!”

North Korea’s government and string of wicked, murderous dictators were indeed an anachronism more befitting the time of Lenin or Stalin or Mao than the era of chic celebrity presidents like Macron and Trudeau and Merkel … well, Macron and Trudeau anyway. This is the kind of wall Democrats would have you believe Trump wants to build: a threatening, barbed-wired symbol of tyranny. Nonsense. Unlike Trump’s proposed wall, this one is meant to keep people in rather than to keep them out. At least, that is the purpose the North Koreans have in mind. For their own part, the South Koreans man their wall defensively. Just as South Koreans aren’t fighting to cross the wire in a desperate bid to reach the communist Utopia of North Korea, Americans aren’t crossing the Rio Grande to take advantage of Mexico’s wonderful social welfare benefits and overturn their electoral process through illegal voting. Trump’s wall is defensive in nature and meant to enforce a sensible immigration policy.

My guide, Don, points into North Korea

Here on the 38th parallel policy is enforced with guns.

Barbed wire.

And a wall.

Don pointed to the north at a gray, misty mountain that lay on the horizon like the ridged back of a dragon.

“Mr. Taunton, can you see those humps in the middle? That’s it. That is why you have come.”

I felt a chill at the sight of the dismal mass rising from the distant plain like Mordor.

* * * * *

As will be apparent to you by now, this is the continuation of The Around the World in 80 Days initiative I began with my team almost two years ago. That project, ambitious in scope and purpose, saw an unsatisfactory interruption. That I did not finish what I set out to do has never sat well with me. But I knew, even then, that I would finish it. So, it is with excitement and a nod toward Him who heals and restores that I tell you that on this day that project resumes, and it resumes here on the 38th parallel.

On the other side of this hill is the barbed wire of the DMZ.

But I didn’t come here merely to talk about border walls against the dramatic backdrop of the most infamous of them that still exist. It is a search of sorts. Over the course of the next week I will tell you an epic story that saw one of its most climactic moments take place here on this blood-soaked ground.

It feels good to be back in the saddle again. Stay tuned.