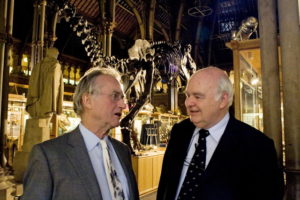

“I don’t usually do debates,” atheist Oxford Professor of Evolutionary Biology Richard Dawkins told John Lennox, himself a Christian and an Oxford Professor of Pure Mathematics and Philosophy of Science.

It was October 3rd, 2007. The two men were backstage waiting to be introduced to a capacity crowd at the University of Alabama-Birmingham’s Alys Stephens Center and a radio audience of well over a million.

“What am I doing here?” Dawkins asked of no one in particular.

“I’ve asked myself the same question, Richard,” Lennox confided. “I think we’ve both been talked into it by that man,” he said, indicating the stage.

“That man” was, of course, me.

Fixed Point Foundation began as a thought in my head. The idea was to engage and educate the public on the “Big Ideas” that dominate our time and to create thoughtful dialogue between representatives of various worldviews. Christians, atheists, Muslims, agnostics, capitalists, socialists, Young Earthers, New Agers, you name it, discussing everything from religion – or the absence of it – to gay marriage and its societal ramifications. But not just for the sake of arguing or entertaining. No, the point was to get at the truth and to let those watching or listening or reading make up their own minds and act accordingly.

The idea was to engage and educate the public on the “Big Ideas” that dominate our time and to create thoughtful dialogue between representatives of various worldviews.

Almost no one, it seemed to me, Christian or otherwise, was doing this or even attempting it. The only chance the public got to hear opposing worldviews meaningfully discussed, if you could call it that, came in soundbites on Fox News or MSNBC where they sat you (literally) in the middle and shouted at you from the right or the left (literally and figuratively). I know. I’ve been that guy who is given only seconds to answer a complicated question:

“Larry Taunton says that it is because Hitler, Stalin, and Mao were atheists that they killed people,” began John Stossel in a Fox News television interview about my book The Grace Effect. “You don’t know that. What do you mean? What about all the Christian Crusaders who killed people?”

Or, in another television interview, this time on Al Jazeera, where the interviewer, Imran Garda, asked, “You say that Islam is a violent religion, but what about the atrocities of your own Christian religion?”

Try to give instantaneous answers to those questions under the lights with millions of people watching. In the first, I was, in effect, to summarize two thousand years of history in a few sentences, and in the second I saw that I would have to deconstruct Garda’s use of the fallacy of false equivalence in a few seconds.¹

Before an interview on BBC Television’s popular show Newsnight with intolerably smug host James O’Brien, I was warned by someone in the know to expect O’Brien to be aggressive and to attempt to misrepresent me and my book: “He will try to prevent you from mounting an effective defense,” came the advice. “When he interrupts, just keep talking. Talk right over him or you’ll never get a chance to speak.” At one point in the interview, that is precisely what I did.

Where I would have liked to have had a serious discussion about the merits of my books, their goal was to do nothing but mischaracterize and discredit.²

This is par for the media course. In such a cauldron, how is one to discuss controversies in sports, much less in religion and politics?

So, I wanted to create a space for sustained engagement on a given issue or idea that was fair, focused, and timed, yes, but allowed for the development of those issues and ideas in a way that existing models (i.e., media) simply did not. Fixed Point was my answer to this problem.

This is important to understand from the outset of this story if you are to make sense of my persistent, dogged determination to bring about the debates and dialogues that are the subject of this series, debates and dialogues that were epic, frustrating, nerve-wracking, often maddening, and always fascinating. The mission of Fixed Point as I have described it above would change as a result of what happened in the debates between Richard Dawkins and John Lennox.

As for whether or not Truth was revealed, that, like the debates themselves, is still being contested all over the world as people watch the films we made of those encounters. The ideologically entrenched remained, unsurprisingly, unmoved as a result of the debates. For them, the saying, “A man convinced against his will is of the same opinion still”³ applies.

But there were others who were moved from one side to the other. I was recently talking to a lawyer who told me that he had just interviewed a young attorney who was an undergraduate at Oxford University at the time of our debate there in October 2008. An atheist and a fan of Richard Dawkins, that debate, he said, caused him deep disillusion and ultimately led him to abandon his atheism and become a Christian.

And the debates reached a massive global audience. On the night of the first debate in Birmingham, Alabama, our website collapsed due to insufficient bandwidth for the more than one million people trying to watch it online.

An atheist and a fan of Richard Dawkins, that debate, he said, caused him deep disillusion and ultimately led him to abandon his atheism and become a Christian.

“Why, it is none other than Larry Taunton!” a woman nearly shouted in a heavy Scottish brogue.

It was August 2008. I was, at that moment, crossing the lobby at the Roxburghe Hotel in Edinburgh. The woman was unknown to me. How could she know my name?

“Hi, ur, uh … you are …?” I stammered, extending my hand.

“I have seen you many times!” she replied. “Our church here in Edinburgh watched your debate between the two Oxford professors!”

She came up and squeezed my face affectionately in her hands and said, “You’re even wearing the same tie!”

I flushed. I felt a bit embarrassed by my limited wardrobe.

Even more remarkably, I was boarding a plane in Beijing in March 2010 when I sat down next to a Chinese woman. The usual get-acquainted-with-your-seat-partner chitchat ensued. At some point, she asked me what I did for a living. Since this was China, I was circumspect.

“I write on hot-button cultural issues and organize academic symposia on those issues.”

I had expected this to put her off. Her eyes would glaze over, I reasoned, and she would bury her head in a book or magazine and avoid further eye contact. But my answer had the opposite effect.

“Really? I am a professor at [I cannot recall the university]. What sort of issues?”

“Well,” I began cautiously (something in her comportment made her seem safe), “for example, we sponsored a debate between an Oxford biologist and an Oxford mathematician on the existence of God …”

She sat forward excitedly. “The debate between the atheist Dawkins and the Christian Lennox?! You did that?! A group of us listened to it on the radio here in Beijing!”

I was taken aback.

“I am a Christian,” she whispered.

I could tell other, similar stories: a woman in the South of France; a group in Auckland, New Zealand; the president of a radio empire; an atheist NFL Hall of Fame quarterback and, separately, a Christian NFL record-holding placekicker; high government officials in Britain and America; and so on.

“Let me save you some money,” the manager of the Alys Stephens Center said as he toured us around the theatre. We were scouting venues for the first – and so far as we knew at the time, the only – debate between Dawkins and Lennox. Standing on the stage, he made a sweeping gesture toward the empty seats and the balcony, and added: “This theater holds 1,250 people. I don’t think you’ll be needing anything more than a classroom to hear your two pointy-heads talking about God.”

The theater had played host to sellout crowds in attendance for performances ranging from Yo-Yo Ma to Tony Bennett. So, an audience of comparable size to hear two “pointy-heads” talking about God struck him as inconceivable. It was a snooze-fest in the making.

I smiled, appreciative of the counsel even as I dismissed it. “I’m gambling that you are wrong.”

But all of this is, as they say, to get ahead of myself.

“Begin at the beginning,” wrote Lewis Carroll in Alice in Wonderland, “and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

In the coming installments, that is what I shall do.