“‘Fixed Point?’ Is that a mathematical organization?”

~ John Lennox, July 2005

I have always said that the backstory to the debates between Richard Dawkins and John Lennox, four in all, is at least as interesting as the debates themselves, if not more so. For every minute that they spent with each other on stage – Richard certainly would not tolerate John’s company anywhere else – I spent many more with each of them off stage. That is because debates of this kind require a lot of planning. You get to know people in these things.

Some of you will wonder if I maintain contact with either of these men. The answer is yes. As many of you know, John Lennox is a dear friend. But that was not the case when all of this began. As for Richard Dawkins, our contact is intermittent and while we are not close, our interactions are friendly enough that we can quarrel and remain cordial. I disagree with Richard ideologically, yes, but I like him. Both men are aware of this series and have contributed thoughts to it. That said, the opinions are my own unless otherwise specified. Hopefully, both will feel fairly treated.

A trip to Oxford and John Lennox

The story starts with John Lennox. Fixed Point Foundation was barely a year old when, in 2005, my board and I decided to step into one of the most explosive issues of that time: Intelligent Design (I.D.). Controversy surrounding this issue was tearing some institutions of higher learning (e.g., Baylor) apart. But it seemed to us that the idea itself wasn’t really being discussed, only the legality of it. Opponents of I.D. didn’t want it discussed. On the contrary, they wanted to suppress any dialogue on it at all. That struck us as both suspicious and unfair. I mean, aren’t universities about ideas? No, as this story will demonstrate. So we wanted to force the issue and find thoughtful representatives to debate it.

Finding someone to argue against I.D. would not be hard. Most university scientists – at least the ones most vociferous and willing to go on record – were against it. Finding someone to represent the positive side of the argument was going to be the real challenge.

As I recall, there were only four serious candidates ever proposed: Michael Behe, Phillip Johnson, Stephen Meyer, and Alister McGrath. Behe is a biochemist at Lehigh and author of Darwin’s Black Box; Johnson was then a U.C. Berkeley Professor of Law and author of Darwin on Trial; Meyer is a Cambridge Ph.D. with the Discovery Institute and was a rising star of I.D. at that time; and McGrath was then the Principal of Wycliffe Hall at Oxford University.

I proposed we get Alister McGrath to represent the pro-I.D. side of the argument. McGrath possesses three doctorates from Oxford University – molecular biophysics, theology, and intellectual history – so his credentials were not in question. Furthermore, he was in the mainstream of evangelical Christianity. Besides, McGrath had been something of a hero of mine during my twenties when my theological views were taking shape. His writing on subjects ranging from church history to atheism had been formative. But I had not read much of his work on science as shall become clear.

My board provided me with the funds I needed and in July 2005 sent me off to a Christian apologetics conference at Wycliffe Hall, Oxford University to bag him. It was with excitement that I arrived. My work and that of Fixed Point still lay in the future. I had published in academic journals but on nothing of mainstream interest. As such, McGrath had no reason to know me or Fixed Point. Before I approached him with our proposal, however, I wanted to hear him speak, so I attended his lectures.

I was deflated. When asked about the Genesis account of Creation, he replied: “Genesis tells us who we are and who we were meant to be.” What did that mean? I didn’t know. Such an answer felt evasive. Moreover, he sounded like a theistic-evolutionist. But even that did not come through clearly. I wasn’t sure what his views were. Before making my transatlantic journey, I had been given a very different account of his convictions by those who knew him. Now I didn’t know what to think.

“Genesis tells us who we are and who we were meant to be.” What did that mean? I didn’t know.

I make no pretense of representing McGrath’s position on this subject. These were just my impressions at the time. But they were strong enough that I knew he was not going to work for our purposes. I decided that my mission was a failure. I had come to Oxford University in vain and at great cost to our fledgling organization. Oh, well, at least the weather was nice and I would go home with a suitcase full of books from Blackwell’s and Waterstone’s bookstores.

Since the conference was paid for and I had no hope of getting my money back at this point, I was determined to derive all that I could from it. I decided to forgo the usual open-top bus tours and punting on the Thames and attend as many sessions as possible, including the obscure ones. One evening toward the end of the week, I made my way into a small, Sunday school-sized lecture hall to hear a presentation simply listed on the program as “Science and Religion.” The lecturer was a fellow named John Lennox. I had not heard of him and he was not presented as a marquee name for the conference and, given where they had placed him in the line-up, they did not make him a high priority.

I sat in a chair in the back nearest the door. Indeed, certain that I would hear a theistic-evolutionist, I sat sidesaddle in my chair facing the door, ready to make a quick exit. There were twenty or so people scattered around the room. Your typical attendee to a conference like this is an American who is there to have a bit of spiritual and intellectual stimulation while touring the English countryside. By this time, most were at restaurants or the theatre.

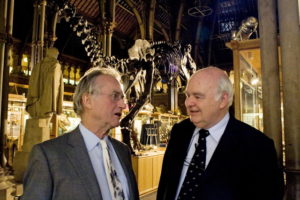

A man in short sleeves and dress pants stood to address the assembled. His shirt was loose at the neck, pens filled his single breast pocket, causing it to sag unfashionably, and a pair of reading glasses hung conspicuously around his neck with as much workplace significance as those of an appraiser of precious stones. White tufts of hair at the sides, unkempt and unacknowledged, completed the picture, framing the pleasant, lively face of this sixty-something-year-old man who flashed a mischievous grin from time to time. If nothing else, he at least looked the part of a professor of mathematics.

No more than five minutes into his lecture I had forgotten any notion of ditching the session in favor of dinner at Bella Italia and a coffee at Waterstone’s. I was fully facing the front, listening carefully to this extraordinary silver-tongued Irishman as he explained various worldviews, how each engaged scientific questions, and why the Christian worldview was not inconsistent with science. He used easily understood analogies and metaphors –Ford’s Model T, Aunt Matilda’s cake, Whittle’s engine – he possessed a good sense of humor, and it was clear that he took the Bible seriously. This room of tired, beaten-down conference goers who had probably attended this seminar in the conviction that to do otherwise was a waste of money, looked invigorated.

Who was this guy and why had I never heard of him? Why wasn’t he speaking in the main sessions? No matter, I knew that I had found my man. It was as if I were a talent scout and had discovered Luciano Pavarotti in an Oxford speakeasy. Now, in a matter of minutes, I had to convince him to come to Alabama.

When he finished his lecture, I waited around politely, hovering until the last person had asked the last question.

“Dr. Lennox,” I began. “My name is Larry Taunton. I am the executive director of the Fixed Point Foundation in Birmingham, Alabama.”

“‘Fixed Point?’” he repeated. “Is that a mathematical organization?”

What? I thought. “Uh, no. We address the Big Ideas convulsing society …”

“Like what?”

“Intelligent Design, for instance. In fact, we were hoping you might participate in a debate on I.D. in Birmingham …”

His eyes shot up. “I don’t do debates, and my work is chiefly focused in Eastern Europe. I really haven’t done much in America.” He mentioned a few states where he had been long ago.

“I’d like to change that,” I said, smiling.

“You need Phil Johnson.”

I shook my head. “Johnson is brilliant. No doubt about it. But he recently suffered a stroke, and we think this debate requires a scientist, not a lawyer.”

He seemed to be in deep reflection. After a moment, he ended the conversation with a line that has since become famous in our friendly banter: “Well, you had better be serious if you want me to come to Alabama.”

He recommended that I go back to Birmingham and, once I had planned something of significance, to let him know.

“Well, you had better be serious if you want me to come to Alabama.”

“I’m quite serious,” I said, wheeling and heading out the door like the man with a mission that I was. Initially, I knew that my chief task would be in convincing my board and supporters, who were expecting the rock star McGrath, that John Lennox, a man they had never heard of, was who they really wanted. As you shall soon see, that wasn’t an easy sell.

What lay ahead was anybody’s guess. An obscure, academic discussion on an issue of little interest to the general public seemed the most likely outcome. Little did I know.

Looking back, I marvel at my naiveté. But I think the Lord knew that to pull this off it was going to take someone of dogged determination and naïve enough to think all of this a perfectly reasonable thing to do. Very soon we would have a university up in arms and AL.com, a newspaper of dubious journalistic merit and an active participant in the culture wars, suggesting that Fixed Point Foundation, with a staff of one and an annual budget of $125,000, was some sort of leviathan manipulating a university’s presidential search process.

And this was just the beginning.