“No matter how high science may be, it is only too clear that Jesus Christ did not come to save men by science or philosophy; he came to save all men — even philosophers and scientists.”

— Etienne Gilson (1884-1978)

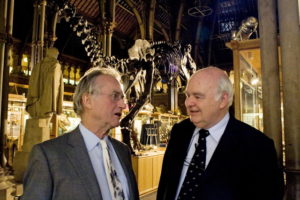

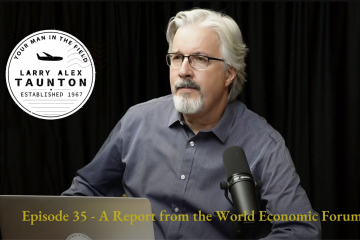

Lennox arrived in Birmingham in February 2006 a few days before the debate on Intelligent Design (I.D.) at Samford University. I had managed to arrange a series of promotional events leading up to the debate: a lecture at the McWane Science Center and the Summit Club; a talk at a local high school; speaking at two churches; and three radio interviews.

The radio interviews were the hardest sell.

“Did you say he is an Oxford mathematician?” the producer asked.

“Uh, yes. But he’s very witty and relatable!”

“Larry, we believe in what you do, man, but, I mean, we are, at the end of the day, about entertaining people. I can already hear people changing the station when we say, ‘next on the show we have an Oxford mathematician!’”

The point was not without merit. I needed an angle, a better pitch for this man. Something to entice show producers. That Lennox would perform well in a radio format I was certain. But that was irrelevant if I couldn’t get him on any radio shows.

“He’s the modern day C.S. Lewis,” I told the next producer with whom I spoke. And the next one after that.

It worked. Mathematics, it seems, conjures too many bad adolescent memories for America’s radio show producers: “Jimmy, come to the chalkboard and solve this algebraic expression.” Brrr. The very mention of Lennox’s profession gave producers shivers comparable to a man who has just been told to open wide for a root canal. Perhaps this is why you don’t see mathematicians scoring many product endorsements where Sofia Vergara and Jennifer Anniston do. Go figure. C.S. Lewis, however, was an Oxford academic who told cute children’s stories and wrote science fiction. Producers could picture him saying, “I don’t always drink beer, but when I do …” He was relatable. Like Lennox. But C.S. Lewis was the ticket to proving it.

During the next few days, Lennox lived up to the promotion that I had given him in the preceding months, and that is saying something, because I had exhausted my supply of superlatives in describing him. Radio audiences, church congregations, and lecture attendees were dazzled by the man’s brilliance.

That word, however, needs some unpacking. John Lennox’s brilliance goes well beyond mathematics or philosophy of science or any other subject. Finding highly intelligent people who believe in Jesus Christ was never the problem, as explained in an earlier installment of this series. The problem was finding someone who could fulfill my expectations the Fixed Point way. You see, it is one thing to possess a deep understanding of a complex field; it is quite another to be able to both explain it to the intelligent layman and to do it in a way that he will find interesting. John Lennox’s brilliance encompasses all three of these skills – like C.S. Lewis. The comparison was not merely a contrived marketing ploy. I believe the comparison to be accurate. And it didn’t hurt that he had been one of C.S. Lewis’s students while he was an undergraduate at Cambridge.

John Lennox’s brilliance encompasses all three of these skills – like C.S. Lewis.

It was during this time that our friendship was formed. Rather than staying in a hotel, John stayed in our eldest son’s bedroom. The same one where Christopher Hitchens would stay a few years later. We added a comfortable chair and table where he could work. Every morning he would eat his usual bowl of Corn Flakes and perhaps a piece of toast with marmalade, and around midmorning Lauri would take a tray of tea to his room. With glasses perched on the end of his nose, he prepared, stopping occasionally to share ideas or to join me for a walk.

Meanwhile, at Samford University the tension was reaching a fever pitch. It was a somewhat bizarre situation with some faculty protesting the debate as a “creation speech” and students playing the role of the reasonable adults who were looking forward to an open and honest exchange of ideas in a university setting. The charge by some faculty that Lennox was an unqualified “crackpot” was dishonest and a strategy that could only be conceived by a genuine crackpot.1

Adding to the bizarre nature of the debate, the faculty committee had refused to provide a single representative to debate Lennox. Instead they had insisted on three, each getting equal time to John. In other words, if John was to get, say, five minutes to respond to a question or 15 minutes in an opening statement, they would each get that same amount – so 15 minutes to John’s five, and 45 minutes to John’s 15.

This made no sense and it was practically impossible. It would make the debate hours long. But that wasn’t all. The faculty committee wanted their debaters to represent three disciplines: law, theology, and biology. Lennox, they said, needed to be refuted in all three disciplines. I refused. I would accept three debaters, and I would accept them being in three different fields. But they would get no additional time and Lennox would ignore anything not related to the science. Since I had University President Tom Corts’s support, I held the high ground and did not need to bow to any of these silly demands. If they didn’t want to debate Lennox fairly, I would go outside the university to find others who would.

The night before the debate, John became very ill. Running a high fever and vomiting, Lauri, who is an RN, saw to his care as best she could but he was clearly in bad shape. Having eaten a bit of too-rare ribeye earlier that day at Mountain Brook Country Club, this had all the hallmarks of food poisoning. All we could do was pray and hope that it ran its course rather quickly.

The next day I waited anxiously for him to emerge from his bedroom. When he did, he appeared to be much improved, but the look on his face suggested all was not well.

“Are you better?” I asked.

Lennox nodded, his mouth turned down at the corners cynically. I waited for it. “Yes,” he croaked. “But I have no voice.” His voice was muted and raspy.

Like Zechariah in Luke 1, Lennox had been struck dumb during the night. Unfortunately, this debate would not be conducted on writing tablets. This was a disaster. Any cancellation at this point and it would look like Lennox had invented an illness for fear of being humiliated in debate.

His voice did not improve as we went from one interview to another. Cutting the last of these short, I took him back to our house. Lauri gave him hot tea with honey and saw to it that he rested.

That evening, hours before the event, the atmosphere on Samford University’s campus was electric. Media, national and local, were already on the scene. Students were queuing up outside of the auditorium along with people who had come from all over the southeast. Cars and vans bottlenecked at the main gates entering the campus from Lakeshore Drive, and people pushed their way into the auditorium when the doors were opened. Cracking a door from behind the stage, I had a fleeting thought that a fire marshal would have been more than a little perturbed by what I saw. Not only were there no empty seats, but people sat on the floor, filling the aisles. Soon the ushers were putting people in the choir behind the stage and on the floor of the stage itself. Then the side doors were kicked open and people sat in a semicircle outside. I could see President Corts sitting shoulder to shoulder with a cadre of university trustees. My own pastor, Bill Hay, said that he sat on the floor in the foyer hugging his knees to his chest. I have often said that it looked like the courtroom scene from To Kill a Mockingbird.2

I closed the door and took a deep breath. All the work, the planning, the preparation – both Lennox’s and my own – had led us to this moment. The next 90 minutes would determine whether the gamble had been worth it.

And it’s at this point that I must break off our narrative.

Yes, the debate went on as planned. Yes, Lennox demolished the lawyer, the biologist, and the former medical school dean who was now a professor of theology. Indeed, Professor Lennox did it with humor, intellect, and style. Yes, the audience loved it and, predictably, the media didn’t.3 But so badly did the debate go for the opposition that one of them pleaded with me, for mercy’s sake, not to distribute video of the event online or in a DVD.

I never did.

I have often questioned the wisdom of that decision, not just for the financial repercussions to Fixed Point4 by canceling production of a DVD but also for the weight Lennox’s presentation would have lent to I.D. in general. But the man was, in spite of Lennox’s obvious gentleness from the stage, so humiliated by his own line of argument that I did not want to add to his discomfiture.5

The debate was spectacular. When Professor Lennox, who was essentially without the powers of speech that morning, first walked to the lectern to give his opening statement, Lauri and I prayed that the Lord would give him back his voice. His first utterances were weak and subdued. But he seemed to gather strength as the debate wore on. After the final arguments were presented, I closed the debate, and the audience gave John a well-earned and enthusiastic standing ovation.

A few minutes later, I stood in the classroom that had been converted into a reception hall. Looking around at the energized people who now packed the place, I paused to take it all in. Samford University students, my volunteers, the Fixed Point Foundation board, and so many others that I did not know were euphoric. Lennox, facing a crush of people who now wanted his autograph, gave me his characteristic sly smile and a wink. Above the din, I heard someone shouting my name. It was Samford President Dr. Thomas Corts.6 Standing on tiptoes, chin in the air the way we do when trying to see over a crowd, he smiled broadly and raised his thumb high in the air, shaking it vigorously while mouthing the words, “well done.”

This whole scene sounds odd, doesn’t it? I mean, it was a debate on Intelligent Design, not the Super Bowl. Who gets excited about that? But such was – and is – the oppression that many feel at the hands of those ideologues who demand absolute adherence to unguided, purposeless evolution. You see, these people are frequently animated by much more than the scientific method; they are aggressively anti-God. Too often they disguise their personal beliefs as science. Lennox had exposed this for what it is: “Not every statement made by a scientist is a scientific statement.” Indeed. And it was students, most of all, who were excited by what had transpired on the stage that night. Lennox had championed their cause and they were grateful for it.

Too often they disguise their personal beliefs as science.

Returning to my house, John and I fumbled around in the darkness. Finding the light switch, I flipped it and a startling cheer went up. A group of students had beaten us home and had been waiting with Lauri and our boys in the shadows. It was that sort of night.

The next day, John was scheduled to speak at Samford again, this time in a chapel service. The auditorium was full to overflowing with students. The faculty, no doubt more than a little humiliated by their mischaracterizations of Lennox and the event the night before, were a no-show. A group of girls sat in the front row with signs with messages like “Marry Me Professor Lennox” and “We Love You!” and so on. It was quite amusing.

Lauri and I drove John to the airport for his flight to London a few days later. We all spoke excitedly of the events of the preceding days. It had been an extraordinary week.

“This is the biggest and best organized thing I have ever done!” Lennox exclaimed. It certainly was for me, too. “But Larry, you must slow down! You have an active mind and you must rest from time to time. The mind is like a rubber band: it will expand and contract, expand and contract, but one day it will expand and not contract again.” I have teased John about the last phrase many times, but the warning, intended to do me good, was on the mark.

All of this was prologue for something much bigger. Without knowing it, Lennox, “The modern day C.S. Lewis,” and I had together stepped through a wardrobe.

“And that,” wrote Lewis, “is the very end of the adventure of the wardrobe. But if the Professor was right, it was only the beginning of the adventures of Narnia.”

The adventure continues to this day.

NEXT INSTALLMENT: RICHARD DAWKINS, THE ATHEIST EVANGELIST

Consider the following: In addition to possessing doctorates in pure mathematics, philosophy of science, and science from Cambridge, Oxford, and the University of Wales, Lennox also possesses a master’s degree in bioethics from the University of Surrey, has published over seventy peer-reviewed papers in pure mathematics, and is the co-author of two research monographs for Oxford University Press. Babers, by contrast, has a master’s degree from Georgia State and a Ph.D. from the University of Georgia.

The point isn’t that Lennox’s academic qualifications, impressive as they are, should have put him beyond scrutiny or that Babers’s degrees are invalid. They are respectable enough. But if I’m Maxwell Babers, I’m not going to attack Lennox’s prestigious academic credentials while a Georgia State degree hangs on my wall. Babers was leading a handful of Samford’s faculty on an embarrassing academic equivalent of the Charge of the Light Brigade with Babers playing the part of the unfortunate Lord Cardigan.

2 Little did Lennox and I know that this was a dress rehearsal for what was to come some twenty months later when he met Richard Dawkins in debate, also in Birmingham, Alabama.

3 Given the Samford faculty’s characterization of Professor Lennox as a “crackpot,” I am confident that the media fully expected to see him make a fool of himself. When the opposite occurred, they took a “nothing to see here” posture and reported nothing or almost nothing. Let me add that none of the faculty had ever met or heard John Lennox before this debate. That fact makes the accusations that much more arrogant and contributed to their intellectual demise in the debate.

4 These debates are expensive, and nonprofits must find creative ways to stay afloat. Prior to YouTube, DVDs were a means of recovering some of the considerable costs for these events.

5 Some months after the debate, I heard that this professor had been dismissed from his academic post. I was sorry to hear this. I invited him to coffee. Reluctantly, he agreed. From the moment we shook hands and sat down, he was angry and resentful. He recalled the debate, the damage it had done to him, and attributed his dismissal to it. I felt genuine compassion for him. We did not want anyone to lose their job. I simply reassured him that we had nothing to do with anything but the debate itself. His participation was voluntary and the arguments he made were his own. I further reminded him that, per his request, I had never made video of the debate public. This answer seemed to satisfy him, and his anger abated.

6 Sometime later, I would have lunch with Dr. Corts. When I told him that I was pleasantly surprised that he had agreed to host the debate, he told me the reason for his willingness: “If you had not been a Samford alumnus with a stellar academic record, I would never have agreed to meet with you to discuss an issue so volatile. But I remembered you as a student and decided to give your proposal a hearing. You convinced me you could do it.” He went on to tell me that a few of the Samford University trustees thought he had lost his mind in agreeing to host a debate on Intelligent Design. “I encouraged them to come to the debate, so they sat with me. I asked for their patience, telling them that Lennox was, as you had told me, the real deal. Once Lennox started speaking, I smiled, knowing he was not going to disappoint. But both of our necks were on the line that night.”