Read Part 1 of this series here

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

The universe that we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but pitiless indifference.”

—Richard Dawkins in Scientific American, November 1995

If Oxford University Professor John Lennox and I had, as I say, stepped through C.S. Lewis’s wardrobe and embarked on a journey together, it remained to be seen where, exactly, we were going. There were no maps to consult, no stars by which to plot our course. But ignorance, as they say, is bliss, and our ignorance was so complete that we didn’t yet know that the Samford University debate was only the beginning of our odyssey. Lashed to the mast, the wind in our sails, we were swept forward to parts unknown.

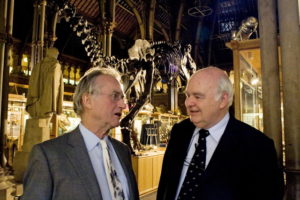

In March 2007, a year after the Samford debate, I was in Oxford to produce our first Fixed Point Foundation film, Science and the God Question. The film featured Lennox and Oxford theologian Alister McGrath and addressed the questions raised by the likes of Stephen Jay Gould, Stephen Hawking, and Richard Dawkins. But it was the latter who was getting the headlines at the time because of the publication of his atheist manifesto, The God Delusion, just six months before.

Lauri and I were in John and Sally Lennox’s Oxford home one evening after a day of filming when I noticed a brochure for the Oxford Literary Festival on a coffee table next to the couch where I was sitting.

“Hey, John!” I called out to the merry mathematician who was then preparing tea for us in the kitchen. “John!” I repeated. “Have you seen this?”

He came stumbling out of the kitchen, tea in hand, no doubt expecting to see the room on fire or a pink elephant – something to justify my excitement.

I instead held up the brochure, displaying the cover announcing that Dawkins would be discussing The God Delusion with McGrath that very night at Christ Church.

“I am going to go to this!” I pronounced confidently.

“You’ll never get in,” he replied dismissively. “It’s been sold out for weeks.”

“I will get in.”

And get in I did. That night, Lauri and I wandered down to Christ Church, one of Oxford’s most beautiful colleges, and found a crowd hoping to get tickets to hear the discussion between the Wycliffe Hall theologian and the New College atheist. The doorman, a security guard of sorts, stood watch before the massive entrance, allowing none without tickets to enter.

“Pardon me,” I said, approaching him. “I am a filmmaker from the U.S., and I am here doing a film with Professor McGrath about his views on Richard Dawkins.” The film was about much more than that, but the rest would do me no good here. “At the time that I made plans to be here in Oxford, I had no idea about this.”

“Do you see all of these people?” he asked. “They are all trying to get in.”

I glanced around. “Yes, no doubt. But it would be a pity to have come all this way and to miss this.”

“Stand here,” he said, his finger pointing to a spot on the pavement. Lauri and I dutifully obeyed.

Minutes before the presentation started, an usher came out and shouted, “We have a few open seats!” There was a surge from the crowd. My new friend, the security guard, pushed people back, and then, pointing at me said, “That man! Him and his companion. Come with me, sir.” We sliced our way through the crowd and were led to our seats.

The place was packed. McGrath and Dawkins sat on stage sharing a table. Before them stood moderator Joan Bakewell, a journalist and presenter for BBC. This wasn’t a debate. It was billed as a discussion on their respective books: The Dawkins Delusion? And The God Delusion. But that doesn’t mean that it was without contentious exchanges. These were, however, mostly one-sided.

McGrath is a man of extraordinary intellect and talent. Read one of his books and you’ll know what I mean. But watching him in this format with Dawkins confirmed my intuition of almost two years before that I would not use the Wycliffe scholar in a debate. McGrath’s talents were ill-suited to a street fight. This was the Leipzig Disputation of 1519 – the rebel priest Martin Luther vs. the papal representative Johann Eck. In that famous encounter, where Luther took each and every question at face value as a serious scholar might, Eck did nothing of the sort. Eck’s singular purpose was to label Luther a heretic. Luther was, in other words, naïve, and he was bludgeoned as a consequence.

McGrath, a serious scholar, was far too accommodating to Dawkins who clearly wasn’t going to reciprocate the friendly overtures and compliments he lavished upon him.

And so it was with McGrath. Dawkins was out to label him a heretic to real science. He heaped scorn upon McGrath who absorbed it all with dignity, but seldom returned fire. McGrath, a serious scholar, was far too accommodating to Dawkins who clearly wasn’t going to reciprocate the friendly overtures and compliments he lavished upon him.

Now I should note here that Richard has read my account of this exchange and has given me insight into portions of it. Indeed, we discussed it today. He simply cannot recall this particular evening, but he would have readers know that he doesn’t bear McGrath any ill will. The two had another, quite cordial, discussion. But Dawkins was, as I remember it, rather annoyed on this occasion. Not only was it his first encounter with McGrath, but he found McGrath’s book, written in response to his own, somewhat offensive. Of course, Christians were deeply offended by Dawkins’s book.

As I listened to the two Oxford academics, I concluded that everything I had previously heard about Dawkins, mostly from Christians, probably wasn’t true beyond his avowed atheism. Dawkins was, they said, simply a sensationalist, an atheist provocateur who said and wrote shocking things to sell books and make money. No more than five minutes into this exchange and I knew this was wrong. Dawkins was a true believer in his dogma. More than that, he was an atheist evangelist out to convert the masses to his way of thinking. I could respect that. Indeed, this was someone with whom I could deal.

An idea began to form in my mind.

I had heard outrageous stories of Christian organizations and high profile Christian “apologists” proposing debates to Dawkins, offering him enormous sums to take them on in places like London, New York, and Boston. Dawkins, according to the rumors, always refused. He was afraid or wanted more money, it was said. This did not ring true as I listened to him on that Oxford evening at Christ Church. Indeed, I wondered if these people had ever bothered to read his book or listen to him at all.

Richard Dawkins isn’t a shrinking violent. He’s the Howard Stern of atheism. And he has courage. Not because he criticizes Christians and their God. Anyone can do that these days. Thanks, in part, to Dawkins, that has become fashionable. But criticizing Muslims and their god in a Britain that is rapidly succumbing to Islam can be a dicey proposition. Trust me when I say that I know what I am talking about here from extensive personal experience. I’ve debated them on CNN, Al Jazeera, and in Hyde Park. They may threaten you. They do this knowing that most Westerners will back down. Richard hasn’t. I commend him for that. As for money, Richard has never struck me as being any more motivated by money than I am. It is a consideration, yes, and he is not indifferent to it, but Richard Dawkins is, I think, motivated by his convictions.

And this is where my predecessors had failed: they had misidentified what makes Richard Dawkins tick. No one listening to this man could reasonably conclude that he was interested in yet another debate with a wishy-washy Christian. Dawkins, I felt, wanted to debate his equal but opposite number – a true believer like him. And he clearly wanted to evangelize. The God Delusion is, after all, an anti-religious tract meant to inspire his fellow unbelievers and convert the religious.

It is, of course, possible that I have transferred to Dawkins what I would want were I in his shoes. I recall some years ago CNN International calling and asking if I would be willing to debate a Muslim on the topics of free speech and antisemitism live on their network. With excitement, I accepted. I wanted to go after a real Muslim – that is, someone who took the Quran and the life of Muhammad seriously – not some fuzzy Westernized Muslim whose beliefs bore little resemblance to Islamic orthodoxy. I assumed that CNN International, which is based in London, and thus had easy access to these “radicals,” would provide me with one. So, what did CNN do? When I went on air I found myself debating a hippie Baptist convert to Islam from North Carolina. Her sensibilities were much more informed by Christianity than Islam. She argued in favor of free speech! When I asked her to name a single Islamic state that permitted free speech, the debate was over. I found the whole thing a great disappointment.

Like me, I felt that Dawkins wasn’t interested in milquetoast Christians any more than I was interested in milquetoast Muslims, and subsequent history seems to confirm that.

Following his discussion with McGrath, I spoke with Dawkins briefly and made the same proposal to him that I had made to Lennox almost two years before:

“Would you be interested in debating your views in Birmingham, Alabama, the buckle of the Bible Belt?”

I had employed the “Bible Belt” designation deliberately, reminding him that it is the hub of evangelical Christianity. If I had read him correctly, he wanted to go into the belly of that beast.

He looked intrigued by the idea. “Whom would I debate?”

It was an obvious question and one for which I did not yet have an answer – only a plan.

“Let me get back to you on that.”

We exchanged email addresses and I told him that I would be in touch.

Returning to our home in Birmingham, I told Lauri what I had in mind. Surprised, she laughed. “Well, I guess you won’t know if you don’t ask. You’ve pulled off the unexpected before.”

I drafted an email to Dawkins and laid out the details of what I proposed: his honorarium, the debate format, potential dates, and so on. Again, he seemed interested, but wanted to know who I had in mind as his opponent.

I didn’t want to seem too eager to see him debate Professor Lennox, not the least because Lennox had no idea what I was up to. So I replied: “Alister McGrath,” knowing full well that he would refuse.

Dawkins’s reply, all in caps, came swiftly:

“IF I AM COMING ALL THE WAY TO BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA, IT CERTAINLY WON’T BE TO DEBATE McGRATH!!”

Sitting at my desk in Mountain Brook Village, I laughed out loud. As I said, Richard Dawkins is not a shrinking violet.

I replied: “How about Dr. John Lennox?”

Again, Richard’s response was not wholly unexpected, because Lennox, an unknown to evangelicals in America, was, perhaps by design, an unknown in Oxford, too:

“Who is that?”

I explained who John Lennox was and why he was appropriate for this debate. Richard, who genuinely did not know Lennox and thus bore him no animosity, preferred that I find a local bishop or a cardinal. But as neither an Anglican nor a Catholic, I didn’t know any such people. Besides, Lennox’s views were much more representative of American evangelicals.

Dawkins consulted his own people via email about my proposal. I know this because his reply unwittingly included the entire internal conversation thread. I will relate only one line from an otherwise unflattering discussion. It came from one of Richard’s younger advisers:

“Double treat for us.”

The treat, it seems, was “double” because not only was I offering them the chance to tell these supposedly unsophisticated Bible Belt Christians that they were delusional, but Dawkins would get paid to do it. From their perspective, it was a double treat indeed.

Dawkins agreed.

A problem, however, remained. Lennox knew nothing about my machinations.

“John, it’s Larry,” I said over the Skype connection.

“Larry, good to hear from you! What are you up to now?”

“Well, John,” I began. “Do you remember that Oxford Literary Festival event featuring McGrath and Dawkins that you said I would never get into? Well, I did get in. And I talked to Dawkins a bit afterward. We exchanged email addresses and I have proposed a debate …”

“You did what?” His voice was excited and not just a little incredulous.

“Yes, I proposed a debate here in Birmingham, Alabama, and, guess what? He’s agreed.”

“You did what?” His voice was even more excited. He called out to his wife. “Sally! You’ll never guess what this man has done this time!”

He returned to our conversation. “Who are you going to get to debate him?” John’s question, naïve and sincere, amused me greatly. He genuinely had no idea. “Are you going to get McGrath to do it?”

“No.”

“[Phil] Johnson? He would be good.”

“As you may recall, he suffered a stroke. And I don’t want a lawyer for this debate.”

“Alvin Plantinga?”

“Negative.”

“Steve Meyer?” I remained silent, so he just kept guessing. “Ravi?”

“No, if I were going to get someone like Ravi, I’d just do it myself. This requires a scientist, not a theologian, philosopher, or the typical Christian apologist.” I was becoming exasperated. Did he really not know?

“Then who do you want to debate him?”

“You!”

“ME??!!” he shrieked. No, he really didn’t know that I had him in mind all along. “Larry, the thing that we did at Samford University wasn’t a serious debate. This is something altogether different that you’re asking me to do. I’m not really a debater. I don’t do debates. That was just …”

I cut him off. “John, you’re perfect. You can do this.” I could hear Sally chuckling in the background.

“What if he doesn’t agree to debate me? And there are other people who are better known and abler to …”

“Dawkins has already agreed.”

“What?! You already told him that I would debate him?”

“More or less.”

He was stupefied. “John, you can do this. I know it.”

“I don’t know it, Larry. Sally and I really need time to think and pray about this.”

“Okay. I’ll give you and Sally a few days to agree to what the Lord and I have already decided.”

I was only half joking. I felt complete confidence in this debate pairing. Dawkins was, in my view, the best representative of the atheistic side of the argument. He was their acknowledged champion. Who better? And John, while an unknown, was perfect because he was a scientist, had theological substance, and was able to communicate the big ideas in a winsome way. That he was unknown was irrelevant. Christians, like everyone else, get too caught up in their celebrities. I knew the Christian public would love John Lennox once they heard him.

And John, while an unknown, was perfect because he was a scientist, had theological substance, and was able to communicate the big ideas in a winsome way.

As most of you know, John Lennox accepted my challenge and agreed to debate Richard Dawkins. In a few short days, news of this debate had rippled across the World Wide Web with great rapidity. Much to my annoyance, I began getting calls from Christian organizations “offering” to take over the event, often insisting that I move it to another city, or urging me to dump Lennox in favor or their own guy.

“Fixed Point Foundation is too small to handle this,” one said.

“Birmingham is a cultural backwater,” another said. “Let us move it to New York.”

“That’s where you’re wrong,” I retorted not just a little defensively. “Birmingham is exactly where a debate of this kind needs to happen. And you can take your New York and …”

Okay, I didn’t actually say that last bit – but I wanted to.

And then there were those who insisted this or that pastor, theologian, or apologist was better suited to the task than the obscure Lennox.

This felt like the infamous meeting with the Samford faculty representatives all over again, and just as I was on that occasion, I was immovable.

“Not a chance,” I said repeatedly.

Since the Samford debate on Intelligent Design, Fixed Point Foundation had doubled in size. Yes, now there were two employees.

I walked into our office and dropped my little bomb on Hannah, who was my assistant, secretary, event planner, administrator, and everything else that I wasn’t. Bright and much more capable than she realized, I would need her to help me manage the details.

“Good morning, Hannah! We are going to do a debate here in Birmingham between John Lennox and Richard Dawkins! And get this: you are going to arrange the details around it!” I didn’t say “hurrah!” at the end of that sentence, but it fit my tone.

Her reaction was not unlike that of Lennox.

“What? I’ve never done anything like that!” She looked panicked. “I don’t know how to do that!”

I had much more confidence in her than she had in herself. “Sure you do, Hannah. You did it a thousand times at Ole Miss.”

This didn’t have the effect I was going for. She simply gave me a dubious look as if trying to recollect planning such an event in “the grove” in a much different Oxford. I tried another angle. “Think of it as a sorority party with a bunch of academics, apologist types, and media – but without the beer and the coeds.”

That, I could see, resonated. She was getting me now.

“Okaaaay … but here? I mean, here in Birmingham? With the atheist Richard Dawkins?”

I smiled at a private recollection: “Yes. Double treat for us.”

2 You can watch that later discussion with McGrath here.

3 This description better describes Christopher Hitchens who was a showman. This isn’t to say that Hitchens didn’t have convictions. He did. Strong ones. But he was nothing like the hardcore atheist Dawkins is. Monetary considerations were more of a driving force for Hitchens.

4 Derived from the Greek word apologia, meaning, “to give a defense,” I dislike this term in its current Christian usage because is largely meaningless to people outside of the faith and to many within it. They are apt to think a “Christian apologist” is someone who goes around apologizing for the Crusades and the Salem Witch Trials!

5 I recently discussed this with Richard, and while he can’t recall specifics, this seemed plausible to him.

6 In 2012, “Christian apologist” William Lane Craig, for not the first time, proposed a debate with Dawkins and Richard refused. To hear Craig’s fans’ telling of it, Dawkins was afraid to debate Craig. I have discussed this with Richard and don’t accept that narrative at all. I think Richard thought it all a bit of circus act lacking in seriousness. That will offend some WLC fans. I do not mean to offend, but the whole “empty chair” tour in Britain struck me as a cheap publicity stunt. Besides, by that time, Dawkins had debated or conversed with Lennox in open forum four times. I didn’t see that Craig could add anything to that discussion. And challenging someone to debate in no way obligates them to accept the challenge.

7 Before I went on Al Jazeera to debate my views on Islam, I received a call from a prominent policy advocate and media personality in D.C. A Christian, he had been on Al Jazeera a year or two before I received my invitation and found the experience deeply upsetting. “Every AK47-wielding terrorist in the world is going to see you,” he said. “They will threaten to kill you. Don’t do it.” He had received such threats, many of them graphic. He strongly advised me to decline the invitation. I took his counsel very seriously, but decided to do the interview anyway. The opportunity to put the Gospel before an audience of 260 million people, to be able to push back at the evil of Islam and encourage persecuted Christians globally, was, Lauri and I felt, worth it.

8 I will defend Richard Dawkins on this charge by saying two things. First, he has never, not once, argued with me about money. He accepted whatever honoraria were offered (always the same as was given to Lennox). Second, as a capitalist, I have no problem with him profiting from his books, lectures, presentations, etc. Good for him.

9 When referring to Muslims, the term “radical” is deceptive. Many of the so-called radicals are not radicals at all. On the contrary, they are quite faithful in their reading of the Quran and the Hadith, and their lives more closely reflect the life of Muhammad, the man they are to model. Islam is an intrinsically violent religion and Muhammad, their founder, was a violent man. “Moderate” Muslims chose to ignore this about their religion – and we may all thank God for it.

WAIT! Do you appreciate the content of this website? We are a nonprofit. That means that our work is made possible and our staff is paid by your contributions. We ask you to consider supporting this important work in an ongoing basis or, if you prefer, perhaps you will drop a few buck in our “tip jar.” All contributions are tax-deductible.