Returning to Birmingham from Oxford, England and my meeting with Richard Dawkins, we went to work preparing for an event that I believed would attract a lot of attention. But not everybody thought that.

“Let me save you some money,” the manager of the Alys Stephens Center said as he toured us around the theater. Hannah and I were scouting venues for the debate between Dawkins and Lennox. Standing on the stage, he made a sweeping gesture toward the dark, empty seats, and added: “This theater holds 1,250 people. I don’t think you’ll be needing anything more than a classroom to hear your two pointy-heads talking about God.”

The theater had played host to sellout crowds in attendance for performances ranging from Yo-Yo Ma to Tony Bennett. So, an audience of comparable size to hear two “pointy-heads” talking about God struck him as inconceivable. It was a snooze-fest in the making.

I smiled, appreciative of the counsel even as I dismissed it. “I’m gambling that you are wrong.”

And it was a gamble. A massive gamble. Fixed Point Foundation operated on a healthy, if not especially robust, annual budget of about $150,000. We could pay our bills and we had never spent a day in the red. But an event of the kind that I envisioned would take some creative financing. Like everything else we set out to do, I wanted it done with excellence. That meant not only the right venue, it meant promotion, ticketing, ushers, security, pre-debate events, a post-debate press conference, building a set for the stage, filming it, and many other things. None of this is particularly difficult if you are CNN or Fox News and you are preparing for a presidential debate. That is because such networks have massive budgets and an army of employees who specialize in doing these things. Fixed Point, however, had nothing of the sort. It was me and my assistant/secretary/event planner/administrator, Hannah. That was it.

Fixed Point, however, had nothing of the sort. It was me and my assistant/secretary/event planner/administrator, Hannah. That was it.

But the details started coming together along with supporters to help finance it all. Perhaps the most challenging part of the event itself was filming it. It’s not as easy as you might think and is probably a great deal more expensive than you’d imagine. Spencer Cooper of Crewsouth agreed to handle this task. Spencer had filmed the Intelligent Design Debate at Samford University for me. However, this was to be something altogether different.

It was Spencer’s idea to use CBS Sports’ film crew and a five-camera shoot: four fixed cameras and one shoulder mounted camera to discretely move about on stage. The CBS Sports guys would sit in their semi-trailer behind the building editing the debate live just as they had done for a thousand Southeastern Conference football games. They would then return it to the auditorium and project it onto improvised Jumbotrons. All of this I agreed to do even as I winced at the $50,000 estimate. If the debate was good, we wanted it preserved in amber.

We then booked rooms for our debaters at the Renaissance Ross Bridge Resort, a beautiful and then-new hotel on the outskirts of Birmingham: a Junior Tower Suite for Lennox and, for Dawkins, the Presidential Suite. Together, if memory serves, these rooms cost us approximately $1,700 per night. Dawkins stayed for only a night and Lennox for a week. Even so, that’s a substantial bill for an organization with our budget.

To some of you, this is an absurd waste of money. I don’t think so. We were planning on having the world’s attention, or a portion of it. This event was not only going to showcase a debate and Fixed Point Foundation, it was going to showcase the city of Birmingham, a much-maligned city. If those watching or listening around the world were expecting something akin to My Cousin Vinny, they were in for a surprise. Furthermore, this was a highly volatile situation. The online chatter about the debate was of the sort that might make a Yankee or a Red Sox fan blush. I was determined to roll out the red carpet for Lennox and Dawkins and treat them far more generously than either might have expected. No one would be able to complain of ill-treatment.

There still remained one important piece of the debate puzzle: who would moderate it? I felt I had too many things to manage offstage to do it myself. Soon, a long line of volunteers were queueing-up at my door to volunteer themselves for the job. But I knew who I wanted: William H. Pryor, Jr. a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit.

But I knew who I wanted: William H. Pryor, Jr. a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit.

Twice elected as attorney general for the state of Alabama, Pryor first gained national attention when President George W. Bush nominated him for the federal bench in 2003 and Senators Ted Kennedy and Chuck Schumer tried to block his confirmation. Pryor, seemingly besieged and unfairly maligned, became the darling of conservatives. Then, a short time later, he again garnered national attention when he prosecuted Alabama Supreme Court Justice Roy Moore for defying a federal court order to remove his now-infamous 5,280-pound granite Ten Commandments monument from the Alabama State Judicial Building. Pryor’s decision to prosecute Moore deeply divided Christians and earned him the ire of evangelicals like James Dobson and Jerry Falwell. But Pryor handled himself well during both of these controversies. What made all of this attractive to me is that while Pryor was well-known to be a man of strong Christian conviction, he had established himself as objective and belonging to no one. I could rely on him to ruthlessly enforce the rules. Not all Christians would be thrilled with him as a moderator and that was precisely the way I wanted it. Judge Pryor, intrigued by the idea, eagerly agreed.

Finally, we had to promote the debate. You can’t fill an auditorium if people don’t know about an event. We had to create a buzz. But how? We had no budget for advertising, and conventional advertising is largely a waste anyway unless you can spend a lot. At that time, my own media contacts were very limited. I didn’t have the numbers of anyone at the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, CNN, Fox or elsewhere in my Rolodex. So I simply flooded their “news tip” email boxes with “DEBATE ON GOD IN BIBLE BELT” in the subject line. I sent dozens to each address. And it worked.

I also called all of the major news outlets. That was a dead end. I quickly discovered they don’t put you through to the news desk when you call the general number and ask for it. Then I had an inspiration. If you call, say, your local internet provider you will get a phone tree: “Press one for billing, two if you are a new customer or would like to add service, three if you are experiencing trouble with your internet …” In a scenario like that, if you press three you will be put into an endless holding pattern. But if you press two – that is, if you’re someone who wants to spend money – you get immediate assistance. So I called the Wall Street Journal and selected the appropriate number for advertising.

“Wall Street Journal advertising, can I help you?” A person!

“I am trying to reach the news desk.”

“Let me transfer you over.”

“Wall Street Journal editorials.” Bingo!

I left a message with someone in that department with whom I had generated some interest. Even though it wasn’t the sort of thing that fell within his assigned field of editorial writing, he told me he would make sure the relevant people heard about it and returned my call.

In a matter of hours, the WSJ was all over it. Naomi Schaefer Riley, then with the WSJ, called and interviewed me. After a quick discussion with her editor, she told me should would be coming down to cover the debate. Once they were in, the sell was easy to other media outlets.

“A theological debate?” one said. “Doesn’t sound like our kind of event.” This felt like the sell for the Intelligent Design debate at Samford University all over again. But the same strategy worked.

“Oh, well, the Wall Street Journal is coming to cover it.”

“The Wall Street Journal is covering it? When is this debate again?”

BBC and NPR were suddenly on board along with The Times (of London). Once the interviews with our participants began, the event sold out in a matter of hours and a kind of media circus ensued.

But this wasn’t disingenuous salesmanship. We believed in this event and what it represented. More than that, we believed in its potential to influence the cultural dialogue on God, specifically the Christian God, in public life in America. Besides, there was a kind of desperation behind our media push because we truly had no money for advertising.

“Hannah, prepare some press packets.”

“I’ve never done that. What’s in them?”

“I don’t know. Participant bios? A bit about Fixed Point? Press passes? Hotel suggestions? Complimentary tickets to Peach Park? Chewing gum? I have no idea. You’re a smart girl, figure it out.”

And figure it out she did.

We believed in this event and what it represented. More than that, we believed in its potential to influence the cultural dialogue on God, specifically the Christian God, in public life in America.

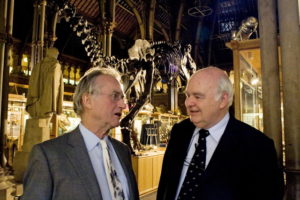

The stage was literally set. It was time to turn things over to our antagonists, Professors John Lennox and Richard Dawkins.

If this debate went as we hoped it would, there was an incalculable potential to push back at the aggressive, blasphemous, hateful, dangerous atheism that continually mischaracterized the Christian faith and was filling the minds of millions of people with nonsense. If it went wrong, the whole thing would, in fact, be a colossal waste of money serving only to contribute to our own demise.

John Lennox, hitherto an unknown outside of pockets in Europe and those who had become acquainted with him that remarkable night at Samford University, was carrying the hope of Christian faith for tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of people.

There’s no pressure in that, right?

WAIT! Do you appreciate the content of this website? We are a nonprofit. That means that our work is made possible and our staff is paid by your contributions. We ask you to consider supporting this important work in an ongoing basis or, if you prefer, perhaps you will drop a few buck in our “tip jar.” All contributions are tax-deductible.