Throughout their histories, Russia and Ukraine have been torn between two factions: Westernizers and non-Westernizers. The Russo-Ukrainian War is a continuation of that centuries-old struggle.

Ukraine’s most famous son is a man whose real name is a matter of some dispute.

It is not Leon Trotsky. We know that dead maniac’s real name was Lev Davidovich Bronstein. (Stalin had him killed by an assassin with an ice ax. Ouch.)

It is neither Nikita Khrushchev nor Leonid Brezhnev, both of whom were also Ukrainian.

Besides, beyond the circles of educated adults or those who lived through the Cold War, few know anything about these Communist icons anyway.

No, the exploits of the fellow I am referring to are well known to youth and adults alike the world over. They have been immortalized in songs sung by Louis Armstrong, Tom Jones, Paul McCartney, Nancy Sinatra, Tina Turner, and Sheryl Crow.

His name was Georgi Rosenblum.

Well, at least that’s what we think his real name was. He was also known as Sigmund Rosenblum, also known as Sigmund Reilly, also known as Sidney Reilly, also known as …

You know him as James Bond.

Or, more accurately, you know him as the basis for Ian Fleming’s fictional character of that name. “Rosenblum, Georgi Rosenblum,” one imagines him saying as he coolly lights a cigarette and adjusts his bow tie before laying down a royal flush in some smoke–filled casino on the French Riviera, men looking on with envy and women with adoration. One of the few surviving photographs of Reilly shows him wearing—no kidding—a tuxedo.

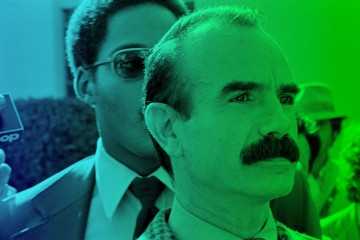

Georgi Rosenblum a.k.a. Sidney Reilly “Ace of Spies”

In 1925, Soviet OGPU (think KGB) agents lured him back into Russia and nabbed him. They thought him a real snappy dresser: “[Reilly wore a] demonstratively elegant suit,” observed one of his captors. Jealous of his Savile Row tailor, they shot him. To honor Reilly, London’s Evening Standard ran a series of articles titled “Master Spy,” glorifying his career. Fleming picked up the story and ran with it. There is some question about whether Reilly really drove an Aston Martin with rocket-launcher headlights or flew a space shuttle full of Amazonians, but one thing is certain:

“He had a gift for deception,” said one biographer.

That’s a nice way of saying that he was a clever liar. Reilly had so many aliases, so many different versions of his past and wartime exploits, that John Kerry would be impressed. Even his biographers cannot agree on the broad outlines of his life. To read two Reilly biographies is to read the biographies of two different men.

And that is fitting given his country of origin, because historians cannot agree on the history of Ukraine. There are two different biographies, so to speak—the Western version and the old Soviet version. The bone of contention is something called the Norman Theory which maintains that the first Russian or Ukrainian state—known as Kievan Rus—was founded neither by Russians nor Ukrainians. Normans, that is, Vikings, founded it.

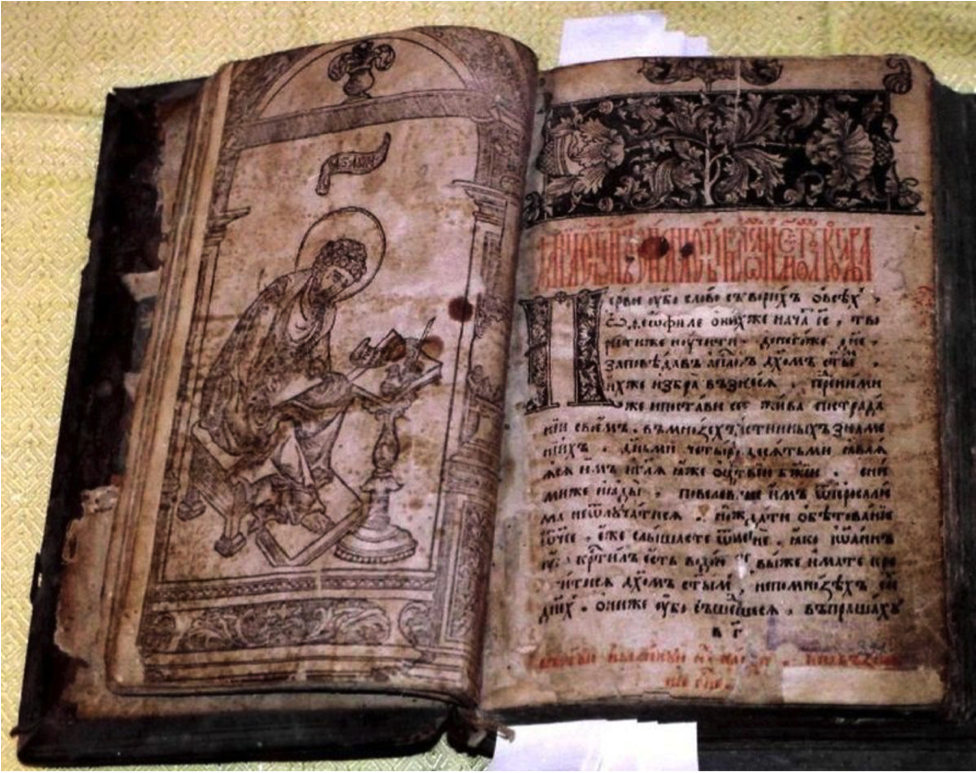

According to The Primary Chronicle, Russia’s and Ukraine’s earliest native historical source, Rus (modern day Ukraine) was so chaotic in the ninth century that a delegation was sent north to the Vikings to request their intervention. Like members of any good chamber of commerce, they made their best pitch: “Our land is great and rich, but there is no order in it. Come and rule and reign over us.”

The Vikings had a bad habit of ruling and reigning over people who had never extended such invitations, so this was an unusual request, to say the least. Still, having laid waste to much of Western Europe, chaos was not new to them. Something like literate Mongols who preferred ships to horses, the Vikings created havoc everywhere they went. But creating order out of disorder was something new.

One imagines them popping a Led Zeppelin CD into the longship stereo as they sailed south: “We come from the land of the ice and snow . . .” Upon arrival, they established what became known as the Rurik Dynasty, after the first king of the new territory, Rurik. Things improved markedly as a result of Viking influence. So much so that Western visitors to Kiev spoke of it as a great and prosperous city. Then the Mongols invaded in 1241. Things went downhill from there. Since then, all efforts to move things back to the top of the cultural hill have been Sisyphean in nature.

So, what’s so controversial about the Norman Theory?

Russians and Ukrainians have never liked the idea that they needed outsiders—Vikings, of all people—to bring order to their land. When Gerhard Müller, the official historian of Imperial Russia, first presented this theory at a meeting of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg in 1749, he was shouted down.

“You dishonor our nation!” he was told.

Afterward, Empress Elizabeth ordered his research seized and destroyed. Perhaps Herr Müller would like to do a little research on the history of Siberia? Gerhard got the hint.

And, until quite recently, that is the way history was written in the old Soviet Union. Not according to what actually happened, but according to official policy. Think of it as Critical Race Theory by another name. Philosopher George Santayana is famously quoted as saying something on the order of, “Those who do not learn from the past are condemned to repeat it.” There was another option that George, a naïve American, overlooked. They can rewrite it. And rewrite it they did. Stalin set the standard, writing some histories himself. Of course, in his own version, he was hero while many others were completely obliterated from the past.

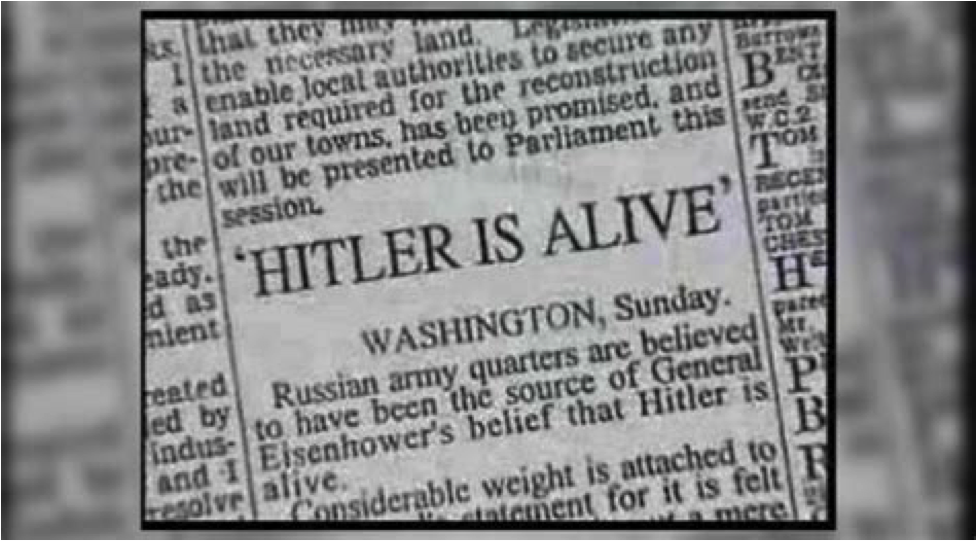

He even changed the present. When the Red Army overran Hitler’s bunker in Berlin in May 1945, Marshal of the Soviet Union Georgi Zhukov told General Dwight Eisenhower that Hitler was dead. Hitler had, he reported truthfully, committed suicide. Zhukov had seen the body. Still, Stalin, preferring another version of events, sent henchman Andrei Vyshinsky, the infamous prosecutor at the show trials, to inform Zhukov of the politically correct view of things.

“Hitler is alive,” Zhukov now told Eisenhower.

Stunned, by this reversal, the Western powers launched a massive Osama bin Laden–like search for Hitler. In spite of the fact that the Russians knew, beyond the shadow of a doubt, that Hitler was dead, this would remain the official Soviet “history” until 1968.

After Stalin’s death in March 1953, Khrushchev denounced Stalin and these policies at a Party Congress. As Khrushchev spoke, a voice from the back of the room allegedly asked why he didn’t criticize Stalin when he was alive. Khrushchev stopped suddenly and bellowed:

“Who said that?”

There was silence. Again, he asked, “Who said that?” Still, no one spoke up. “Now you understand,” he said.

Russia and Ukraine suffer from great identity crises so thoroughly has the past been written, rewritten, or altogether annihilated. Consequently, society stumbles along in a schizophrenic manner, locked in a tug-of-war between two domestic groups: the Slavophiles, a xenophobic group that detests Western influences and prefers what they considered The Russian Way as the best path forward, and the Westernizers, who want to adopt a Western form of government, society, and in some cases, even Western styles.

A quick romp through Russian (that is to say, Ukrainian) history since the late seventeenth century will demonstrate just how schizophrenic these countries are:

Tsar Peter the Great

Peter I (1682-1725): Westernizer

Peter, otherwise known as “the Great,” was determined to drag Russia into the modern world kicking and screaming if need be. He made two great tours of the West and brought back to Russia Westerners skilled in everything from the art of war to shipbuilding. He even required the Boyars (noblemen) to shave their beards. Those who refused had to pay a “beard tax.”

He was followed by a series of lackluster rulers who oscillated between Slavophilism and Westernizing until …

Catherine II (1762-1796): Westernizer

Catherine, otherwise known as “the Great,” was a German princess-turned-“Empress of All the Russias.” After the murder of her husband in which she is alleged to have taken part, Catherine endeavored to modernize her new homeland. She did, that is, until the French Revolution, which saw the beheading of King Louis XVI and his queen, Marie Antoinette. That made her—and every monarch at the time—more than a little nervous. Probably the only intellectual to sit upon the throne of Russia, Catherine demonstrated her agile mind in a correspondence with Voltaire where the two discussed Enlightenment ideals.

Paul I (1796-1801): Slavophile

Son of Catherine and an immense mediocrity, Tsar Paul hated his mother, and he attempted to undo her reforms.

Alexander I (1801-1825): Westernizer

Immortalized by Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Alexander presided over the Napoleonic Wars. Although he was the son of mercurial Tsar Paul, he was a man of refinement who possessed the disposition and characteristics of his grandmother, Catherine. Like her, he made tentative efforts to Westernize.

Tsar Alexander I

Nicholas I (1825-1855): Slavophile

Nicholas, Alexander’s much younger brother, began his reign in grand Slavophile fashion: by crushing a revolt led by a group of Westernizer army officers known as the Decembrists. Men who had seen the enlightened West during the Napoleonic Wars, the Decembrists wanted to build on Alexander’s modest reform efforts. Nicholas was having none of it. A reactionary, he feared the general demise of Russian autocracy amidst the revolutionary movements then sweeping Europe. Thus, he became harsher in his rule, refused to liberate the serfs, and plunged Russia into the disastrous Crimean War.

Alexander II (1855-1881): Westernizer

Known as “the Liberator Tsar,” Alexander came to the throne at the height of the Crimean War—note that Crimea is a constant theme in Russia’s history—a war that had laid bare Russia’s perpetual backwardness. Liberally educated at the instruction of his intelligent (and Western) mother, Alexander earned his moniker by doing the unthinkable: he freed Russia’s serfs. Russians, at least the ones who know their history, love to point out that Russia freed its slaves before America freed her own. In any case, the Westernizing trend was halted when Alexander was blown to pieces by terrorists who thought his reforms insufficient. They demanded the abolition of the monarchy.

Alexander III (1881-1894): Slavophile

Gruff and poorly educated, Alexander was a hardcore Slavophile who took the assassination of his father as proof that one must rule his subjects with an iron fist. This was a period that saw the expansion of the secret police, closing Russia off from the West, and a general purge of Western influences.

Nicholas II (1894-1917): Slavophile

Known chiefly as the last tsar of Russia, Nicholas might not have been known at all had he not become tsar at one of the most volatile periods in Russia’s history. Lacking the temperament, education, and experience to rule this vast land, Nicholas fell prey to his foolish wife, Alexandra, who was desperate to save their hemophiliac son. History records that this led them to the fatal counsel of a starets named Rasputin. Westernizing might have saved him and his family, but if his father had taught him anything it was that liberalization was a dereliction of a God-given duty and a sign of weakness. Nicholas, Alexandra, and their children—Olga, Maria, Tatiana, Anastasia, and Alexei—we all executed in “the house of special purpose,” their bodies mutilated and then deposited in a mine shaft.

The back-and-forth theme did not end with the coming of the Bolsheviks.

While neither Lenin nor Stalin or any of their immediate successors were Westernizers as it is commonly understood, they did readily perceive Russia’s backwardness, and stole from the West everything from the B-29 and the space shuttle to McDonald’s and the atomic bomb.

Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin, however, were both Westernizers, each in their way trying to close the gap with the West.

Putin is a Slavophile. Not only has he rejected the West, he mocks it—and not without some justification:

There are some monstrous things when, from a very young age, you teach to children that the boy can easily become a girl and you impose on them this selection, this choice. You push the parents aside and make the child [make] this decision that can destroy their lives. And if we call the spade a spade, this is nigh to crime against humanity and all of that under the banner of progress …

This is used as proof that the West offers nothing worthy of emulation. Old Russian ways are best for Russians—or so goes the logic.

For their own part, Russian Westernizers tend to agree with a sentiment expressed by the late Russian historian Sir Bernard Pares: “It was no use assuming that Russian plans worked out well for Russians: they did nothing of the kind; Russians made failures of everything and reveled in failure.”

The Russo-Ukrainian War is, in a sense, a continuation of the centuries-long battle between Westernizers and Slavophiles insofar as Putin is determined that Ukraine, Russia’s breadbasket, warm-water port, and buffer state, will not end up in the bosom of the West and its myriad of liberal influences.

So, the next time you hear “Bond, James Bond,” just remember that it was really “Rosenblum, Georgi Rosenblum.”

Maybe.

Because we have no more cracked the riddle of who that guy was than we have the enigma that is the always controversial, often bizarre, and invariably murky histories of Russia and Ukraine.

Past Is Prologue: A Series on Russian/Ukrainian History | Part One: Not With the Mind

If we hope to even begin to understand Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we must know something of the complicated history of these countries. It was against the backdrop of the collapse of the Soviet Union

Past is Prologue: A Series on Russian/Ukrainian History, Part II “Shaken, Not Stirred”: The Schizophrenic National Identities of Russia and Ukraine

Throughout their histories, Russia and Ukraine have been torn between two factions: Westernizers and non-Westernizers. The Russo-Ukrainian War is a continuation of that centuries-old struggle.

Larry Alex Taunton is the Executive Director of the Fixed Point Foundation and a freelance columnist contributing to USA Today, Fox News, First Things, The Atlantic, CNN, Daily Caller, and The American Spectator. He is also the author of The Grace Effect, The Gospel Coalition Book of the Year The Faith of Christopher Hitchens, Around the World in (More Than) 80 Days. (Available to order now) You can subscribe to his blog at refined-badger-e0ceb8.instawp.xyz and find him on Twitter @larrytaunton.

WAIT!

Do you appreciate the content of this website?

We are a nonprofit. That means that our work is made possible and our staff is paid by your contributions. We ask you to consider supporting this important work in an ongoing basis or, if you prefer, perhaps you will drop a few bucks in our “tip jar.”

All contributions are tax-deductible