If we hope to even begin to understand Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we must know something of the complicated history of these countries.

It was against the backdrop of the collapse of the Soviet Union that I, as an undergraduate getting a degree in European history, decided to pursue the study of that subject at the graduate level. But with one slight modification: I would make Russian history an area of concentration. Indeed, as Boris Yeltsin stood atop a tank facing down Soviet hardliners in the failed August Coup of 1991, I was boarding a KLM flight to London to continue my studies there. I was going to the city of not only Henry VIII and Churchill, but of the exiles, Marx and Lenin.

I was not without some doubts. I recall vividly my academic advisor, possibly mindful of his own genteel poverty, telling me that I should abandon the study of Russian history and become a writer or attend law school. Degrees in history are of questionable economic value in the best of times, but with the theoretical ending of the Cold War, Russian experts and those conversant in Marxist thought, valuable commodities for 40 years, would be a dime a dozen. Marxism, to use the term then in vogue, was “a discard on the ash heap of history.”

“There are still a billion people on the other side of the planet who would argue with that assessment,” I replied with more confidence than was warranted.

“China is a geopolitical irrelevance,” came the retort. I winced. I had submitted an essay—in those spartan days my personal economy was partially funded with monies won in essay contests—on how China, not Russia, was the greatest threat to global security. It was mostly a load of sophomoric nonsense. But it now seems I was on to something if only in the broad strokes.

I share this bit of personal history because it offers insight into the prevailing academic view thirty years ago. It was a view that trickled down into the media and pop culture. The Scorpions—yes, the West Germany head-banger band of “Rock You Like a Hurricane” fame—encapsulated the cultural moment with the song Wind of Change:

The wind of change blows straight

Into the face of time,

Like a storm wind that will ring

The freedom bell for peace of mind,

Let your balalaika sing

What my guitar wants to sing.

About the time that I was buying a pirated CD of this song in Red Square of all places, political theorist Francis Fukuyama was publishing his bestseller The End of History and the Last Man in which he argued that Western liberal democracy had triumphed and now it was just a matter of mop-up operations against the remaining pockets of resistance. (You know, China, the Middle East, and the whole of Africa for instance.)

Former New York Times Moscow Bureau Chief and Pulitzer Prize winner Hedrick Smith published The New Russians in which he said something not too dissimilar. The dissolution of the Soviet Union was “a modern enactment of one of the archetypal stories of human existence, that of the struggle from darkness to light, from poverty toward prosperity, from dictatorship toward democracy.”

According to the talking heads, we were witnessing something akin to the Domino Theory in reverse: instead of nations falling like dominoes to communism, they were falling, one by one, to freedom movements.

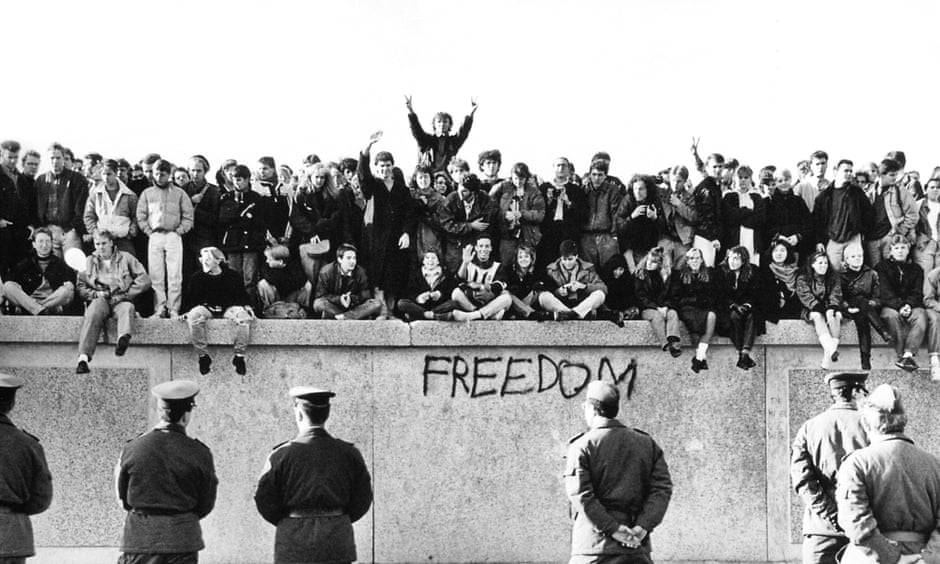

These are snapshots of the period, don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. A wave of freedom euphoria was then washing over the West. Young, naïve, and idealistic, I was swept up in it. Seeing those brave people chipping away at the Berlin Wall in November 1989 set something off in me. I wanted to be on that wall with them. More than any other historic event in my lifetime, that one shaped my personal destiny. I was inspired to study history, to write it, to play a role in it. I was, as I said, idealistic.

Cue the sad trombone: wah wah wah waaaa

Within a few short years, the shine of the moment was off, and the euphoria was gone from presidents, prime ministers, and rock bands alike. Citizens of the former Federal Republic of Germany—a.k.a., West Germany—were resentful of the enormous cost of assimilating the former German Democratic Republic (GDR)—a.k.a., East Germany. West Germans were also recognizing what The Scorpions had missed: 45 years of communist rule had not only left the East in shambles, it had fundamentally changed them as a people. Socialism had killed the work ethic and efficiency so often assumed to be innate to Germans. Worse, they were like children who had been raised in a household where authority was exercised randomly, irrationally, and brutally. Communist rule had assassinated them spiritually.[1]

“We don’t want them,” one bitter man told me over his beer in Munich shortly after reunification. “They’re no longer German.”

These problems went well beyond the former GDR. Throughout the old USSR, in satellite countries like Ukraine, one found people who were having doubts about freedom, a concept that is alien to their historical experience. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union with it, everything from Christian missionaries and capitalists to Scientologists and Mormons began flooding into the former East Bloc. Naïve to the complexities of Western notions of freedom, citizens of these countries eagerly consumed all of it—at first.

But after an initial openness, the window of opportunity started closing. Many in the East felt they had been burned by the West’s corrupting elements. Freedom, they decided, was overrated. It was anarchy, and it required too many personal responsibilities and choices. In spite of Fukuyama’s, Smith’s, and the Scorpions’ cheery assessments, the pendulum started swinging back in the other direction.

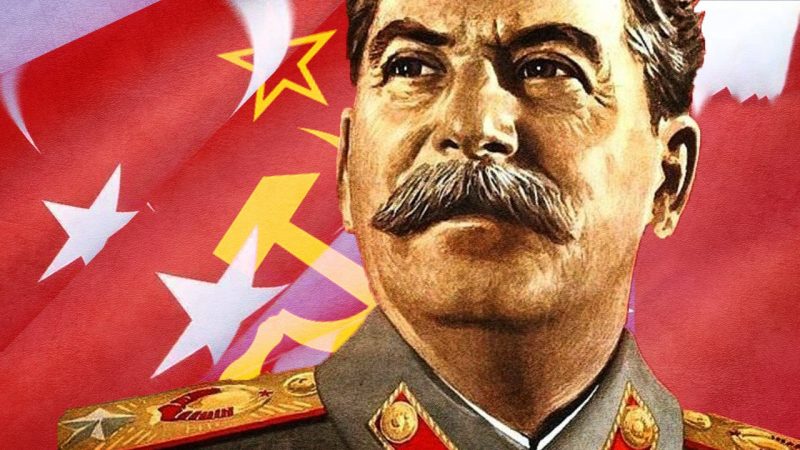

It became harder for Westerners to operate in Russia, Ukraine, and in almost every other old Soviet satellite country. It is true that some were making the transition to Western-style democracy and free markets better than others—Czech Republic and Poland are two—but in others there was a rising nostalgia for the iron-fisted days of Stalin when the USSR was respected and feared, and one simply did what he was told to do.[2] Old communists like Putin, so unpopular in the waning days of the Soviet Union and in the immediate aftermath, waited for their moment. The Israelites would soon want to return to Egypt. After all, hadn’t Dostoevsky predicted in The Grand Inquisitor that people, especially Russians, would exchange their freedom for security? “Make us your slaves, but feed us.”

That trend, from totalitarianism to a fragile freedom and back again, has continued to this day. The difference, I can tell you, in the feel from Russia in the early 90s to now is profound. Russia in the 90s was like the Wild West, but hopeful. Russia today feels a bit like Trudeau’s Ottawa: better be careful where you park that truck.

What, you ask, does this have to do with Ukraine?

First, the histories of Russia and Ukraine cannot be told separately. They are, for better or for worse, Siamese twins. One simply cannot escape the other. The first Russian/Ukrainian state, known as Rus, was founded in Kiev. Khrushchev was Ukrainian. So was Brezhnev. Begin to see the problem? This isn’t Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine and, barring a nuclear war that puts an end to us all, it won’t be the last.

Second, as you try to navigate the 24/7 news cycle on the war in Ukraine, bear in mind that some of the agencies and people who were driving the media narrative and shaping foreign policy then, are the same agencies and people who are driving the media narrative and shaping foreign policy now. Western analysts have almost always been spectacularly wrong in understanding the Russian mind and its motivations. They were then, they are now. When the Russians fail to act as the “experts” think they ought, they label them “crazy.” Have you seen that narrative circulated about Putin? It’s everywhere.

For analysts operating in their pretentious think-tank echo chambers, the only explanation for them being wrong about what Putin would do regarding U.S. meddling in Ukraine is that Putin is insane. And yet, one of the most basic facts of Russian history says that Russia has always regarded Ukraine—not Estonia, Latvia, or Lithuania—as integral to Russia’s existence. Did no one at the State Department tell the Obama and Biden administrations that? Or did they just not know it?

The “crazy” narrative being pushed on every network is the same one that was pushed about all of America’s enemies—the Ayatollah, Saddam, bin Laden, etc. It is intellectually lazy. Rather than looking for the connective logical tissue and trying to understand what motivates them, we punt, dismissing them as beyond understanding. It looks oddly similar to what many men do when they find themselves in conflict with the women in their lives. If it’s not a winning strategy in personal relations, what makes us think it’s a winning formula in international relations?

Take, for example, 9/11. The terrorists must be nuts, we were told. What sort of person would kill themselves and others like that? Understood from a purely secular point of view where there’s really nothing worth dying for since this life is all you get, the crazy explanation seems the right one. But the secular key didn’t fit this lock because these men weren’t secularists. When September 11th is viewed through the lens of the teachings of the Quran, the Hadith, and the life of Muhammad, the tumblers line up and it becomes, for a Muslim seeking Allah’s favor and eternal life, a perfectly rational act. One need not be crazy to commit extraordinary evil. This is Hannah Arendt’s “banality of evil” thesis.

Finally, I offer a corollary. Part of what we will be trying to unravel in this series is not only the shared history of Russia and Ukraine, but the West’s (largely disastrous) interactions with both.

Western foreign policy, particularly that of the United States, has often operated on the erroneous premise that we are dealing with people who want the same things we do: freedom, peace, and a car in every garage. Such thinking got us nowhere with “Uncle Joe” Stalin and Ho Chi Minh and it’s getting us nowhere with Xi and Putin.

Those countries that are not heirs to a Western tradition of thought don’t think like Westerners. And while human nature is the same the world over, human motivations, influenced as they are by a plethora of cultural factors ranging from historical experience and geography to religion and philosophy, are not.

Consider the fact that neither Russia nor Ukraine ever experienced the Renaissance, Reformation, Enlightenment, Scientific Revolution, or Industrial Revolution. These epochs defined the West as we know it and define Western thinking. Not Russia, not Ukraine. Even those Russian writers embraced by the West—Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Solzhenitsyn most of all—are little understood by it. This is evidenced by the fact that while they are loved in the West, that love was unrequited. All of them rejected the West as soft, decadent, and a great spiritual void.

Churchill called Russia “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma,” and to the Western mind it is. But to many Russians (and Ukrainians), such thinking is typical of arrogant Westerners. I am reminded of the poem Not With the Mind (1866) by Fyodor Tyutchev:

Not with the mind is Russia comprehended,

The common yardstick will deceive

In gauging her; so singular her nature —

In Russia you must just believe.

Any discussion of Russian history must begin with this: the way you think, dear Westerner, will not be helpful here. Keeping this always in the back of our minds, we begin our series.

Watch for Part 2 of this series to drop soon.

[1] Anna Funder’s Stasiland is a superb exploration of this subject. Funder went to the former GDR and interviewed Germans who had lived under communist rule. The stories she relates are often powerful and moving.

[2] A poll in Ukraine found that 16 percent of Ukrainians wanted to return to the days of the Soviet Union.

Past Is Prologue: A Series on Russian/Ukrainian History | Part One: Not With the Mind

If we hope to even begin to understand Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we must know something of the complicated history of these countries. It was against the backdrop of the collapse of the Soviet Union

Past is Prologue: A Series on Russian/Ukrainian History, Part II “Shaken, Not Stirred”: The Schizophrenic National Identities of Russia and Ukraine

Throughout their histories, Russia and Ukraine have been torn between two factions: Westernizers and non-Westernizers. The Russo-Ukrainian War is a continuation of that centuries-old struggle.

Larry Alex Taunton is the Executive Director of the Fixed Point Foundation and a freelance columnist contributing to USA Today, Fox News, First Things, The Atlantic, CNN, Daily Caller, and The American Spectator. He is also the author of The Grace Effect, The Gospel Coalition Book of the Year The Faith of Christopher Hitchens, Around the World in (More Than) 80 Days. (Available to order now) You can subscribe to his blog at refined-badger-e0ceb8.instawp.xyz and find him on Twitter @larrytaunton.

WAIT!

Do you appreciate the content of this website?

We are a nonprofit. That means that our work is made possible and our staff is paid by your contributions. We ask you to consider supporting this important work in an ongoing basis or, if you prefer, perhaps you will drop a few bucks in our “tip jar.”

All contributions are tax-deductible