(NOTE: This series originally appeared in The Daily Wire.)

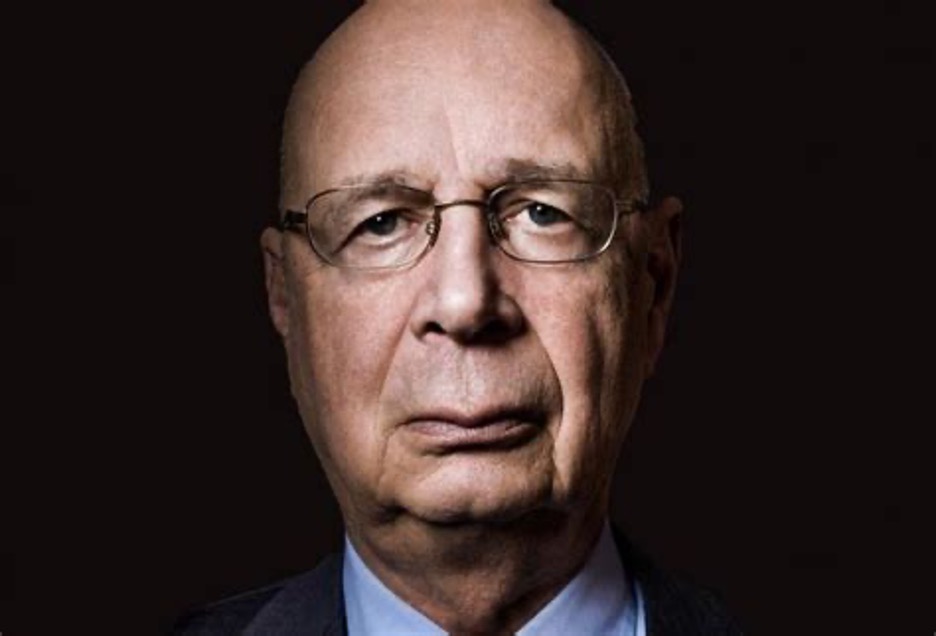

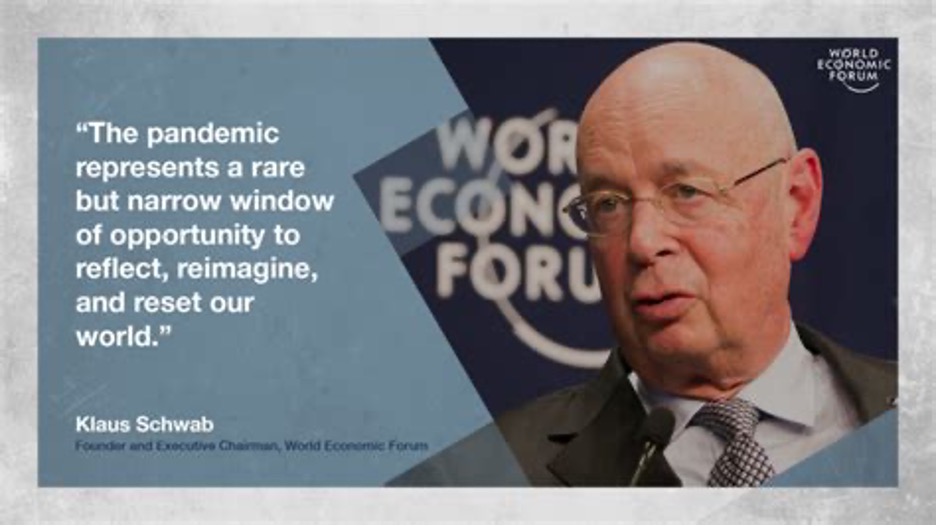

When I began researching this series for The Daily Wire a couple of months ago, I scarcely knew the depth of the rabbit hole into which I would descend. What started as a straightforward article about the octogenarian German engineer Klaus Schwab and his brainchild, the World Economic Forum, an organization he has chaired since its founding in 1971, soon took on increasingly complicated dimensions involving academic papers on world governance and population control, UN reports on poverty, discussions of data and transhumanism, numerous conspiracy theories, world leaders, billionaires, obscure think tanks, and gargantuan ideas with egos to match them.

Where to begin?

And then it dawned on me. To understand Schwab and the World Economic Forum (WEF), the place to start isn’t Davos, Switzerland, where members of the forum and hangers-on meet annually. It’s Utopia.

Oscar Wilde once said that a map without Utopia on it wasn’t worth consulting.

Utopia, it was long assumed, lay in the distant past. The Hebrews called it Eden. A garden of innocence and spiritual perfection until man spoiled it. The Greeks, too, looked backward. With a kind of law of entropy at work in history, Plato and centuries of successors believed that the further one went back in time, the more perfect things became until one reached a Golden Age at the dawn of civilization. He spoke of a city called Atlantis. Some, taking his allegory seriously, tried to find it, having no more success than Pizarro in his vain and bloody search for El Dorado.

But it was with the Renaissance and Thomas More, who gave us the word Utopia—of Greek construction, it means “no place”—that a seismic shift occurred. No longer was the perfect state a prehistoric city (or cities as More conceived it) representing the highwater mark of a lost civilization, but it was very much in the present—and in the future. Henceforth, “Utopians” possessed by the idea of eternal progress and the perfectibility of human society if not humans individually, would seek to build it.

There arose in the Renaissance and the Enlightenment a spate of utopian visions for the betterment of man. And, then, with the human degradation of the Industrial Revolution, came the greatest—in body count—utopian vision of all: Marxism. Promising to sweep away injustice, hunger, poverty, and suffering, “scientific socialism” gathered up adherents, especially the young, who, in the post-The Origin of Species (1859) world, were looking for a new religion to replace the old one.

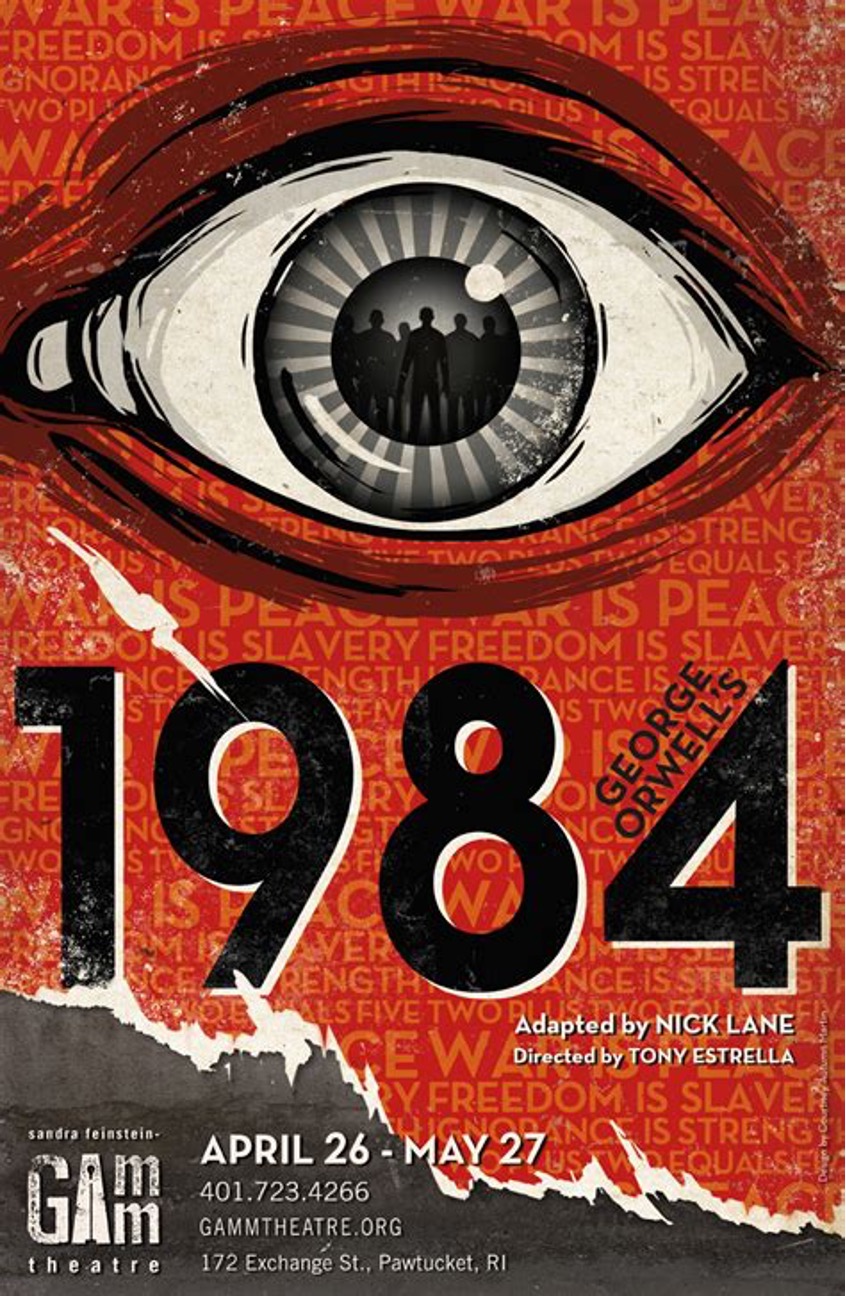

Victorian novelist and critic Samuel Butler, who saw better than most the logical flaws in Charles Darwin’s epoch-defining work, also saw the inherent dangers of megalomaniacs and their undeliverable promises of paradise. In his anti-utopian novel Erewhon (1872)—an anagram of “nowhere,” a play on the very definition of Utopia—Butler warned of the temptation to surrender freedom to clever philosophers who would convince them that their institutions were unjust and that they alone could fix them.

Butler needn’t have bothered.

The promise of a perfect world, and the intellectuals of the day said it was possible, was far too alluring. And, so, the competition to build it was on. But unlike More’s and Plato’s imaginary creations, these would-be utopias were all too terrifyingly real. At the same time that Lenin was building his utopia on the millions of Russian dead, Henry Ford was planning his model city (modestly named “Fordlandia”) in the interior of Brazil. Certain that progress was as much a constant of the universe as the laws of thermodynamics, the twentieth century saw roughly half of the world wrecked by merely that promise.

If utopia once meant a perfect or ideal society, subsequent attempts at achieving it freighted the word with an altogether different meaning: unworkable. By the end of the last century, Marxism and its twin fascism would kill more than 150 million people. But utopians are seldom put off by body count, and so the experiment was repeated in the people paradises of Cuba, China, North Korea, Venezuela and many more besides. George Bernard Shaw, a hardcore communist in addition to being a playwright, spoke for more than himself when he said after a visit to Stalin’s Russia: “It’s not a question of to kill or not to kill. It’s a question of killing the right people.”

The road to Utopia always seemed to run through a field pitted with mass graves.

Offering an explanation for the endless appeal of utopian dreams in spite of the extraordinary human toll, the late Karl Popper, a professor of philosophy who, ironically, taught George Soros at the London School of Economics, wrote: “I am inclined to think that the reason is that they give expression to a deepfelt dissatisfaction with a world which does not, and cannot, live up to our moral ideals and to our dreams of perfection.”

But today, with so many failed attempts at societal bliss ending like a familiar James Taylor song—“Sweet dreams and flying machines in pieces on the ground”—and not one country, city, town, or village to which we can point and say, See! There lies Utopia! we know better, right?

Wrong.

I give you Klaus Schwab and the World Economic Forum.

“The future is built by us!”

This might come as a surprise to the planet’s remaining eight billion people who have not elected Schwab to so much as city dog catcher. Yet, it was without any sense of irony or embarrassment that Schwab, like a true utopian, made this declaration with a brandished fist. One may reasonably deduce from this that Schwab is not an avid reader of Samuel Butler—or, for that matter, of Aldous Huxley, George Orwell, or the Bible. The statement was at the heart of his opening remarks for the May 2022 gathering of the WEF’s annual meeting in Davos.

The WEF’s motto is not lacking in ambition: Committed to improving the state of the world. Most of us content ourselves with more modest goals, like, say, improving your credit score or golf handicap. Regardless, the WEF’s attitude toward democracy (contempt), national sovereignty (passé), patriotism (fascist), business (should be government run), and personal liberty (selfish) suggests a different agenda than world improvement. Whatever your theory on their goals, they can, says Schwab, be achieved “by a powerful community as you here in this room.”

And powerful they are. More than fifty heads of state attended this year’s meeting. Add to this the leadership of Alibaba, Blackrock, Google, Microsoft, and many other captains of industry and you have an eyebrow-raising convocation of powerbrokers—collectively known as “Davos Man,” a term coined by political theorist Samuel Huntington—to rival any international assembly.

Like progressives everywhere, they profess a love of man—but in the abstract. Instead of helping the person in front of them as in the Christian model, they would save the hypothetical millions, or, in this case, billions. It’s either solve world hunger, poverty, and inequality or nothing.

And according to Vanity Fair’s Peter S. Goodman, it’s nothing. In an interesting plot twist, he sees Davos as a sinister expression of right-wing politics as if Schwab’s devotees were all MAGA-hat-wearing conservatives. Goodman neither condemns Schwab nor his WEF for their subversive globalist agenda; he condemns them for their hypocrisy in not fulfilling it:

In the prevailing pantomime, Davos Man is intent on channeling his intellect and compassion toward solving the great crises of the age. He might have retreated to his mountaintop palace in Jackson Hole or his yacht moored off Mykonos, but he is too obsessed with rescuing the poor and sparing humanity from the ravages of climate change. So he is in Davos … posing for photos with Bono, congratulating Bill Gates on his philanthropic exploits, tweeting out inspirational quotes from Deepak Chopra …

In other words, Davos is a lot like Martha’s Vineyard. I’m reminded of a line from Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov: “The more I love humanity in general, the less I love man in particular.” Humanity, in the progressive view, is best loved from afar. As in, when the National Guard takes the brown-skinned undesirables away or, as here, from atop a Swiss alp.

But all of this begs prior questions:

Who is Klaus Schwab?

What exactly is the World Economic Forum?

What is the ideology driving them?

And what is “The Great Reset”?

These things will be discussed in subsequent installments in this series. Until then, remember that Herr Schwab has your future all planned out for you:

WAIT! Do you appreciate the content of this website? We are a nonprofit. That means that our work is made possible and our staff is paid by your contributions. We ask you to consider supporting this important work in an ongoing basis or, if you prefer, perhaps you will drop a few buck in our “tip jar.” All contributions are tax-deductible.